![]()

*This image is copyright of its original author

The Tasmanian devil once thrived on mainland Australia. Shutterstock/mastersky

The

Tasmanian devil – despite its name – once roamed the mainland of Australia. Returning the devil to the mainland may not only help its

threatened status but could help control invasive predators such as feral cats and foxes.

The idea of returning devils to the mainland has

been raised before.

Read more: Tasmanian devils reared in captivity show they can thrive in the wild

But now we’ve explored the idea from a palaeontological view. We looked at the fossil record of mainland devils, in a

paper published online and in print soon in the journal Biological Conservation.

![]()

*This image is copyright of its original author

A well preserved devil mandible (lower jaw) recovered from excavations west of Townsville. Gilbert Price, Author provided

The fossil record helps us better understand how the devils co-existed on mainland Australia with other wildlife. It also helps us see how these iconic animals may possibly interact with small and medium-sized animals if reintroduced to the mainland in the future.

Back in the wild

Ecologists have reintroduced several apex predators to environments where they were once driven to localised extinction. This has helped restore past ecosystems by providing a clearer ecological balance.

One of the best-known examples is the

reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the United States, to check the overgrazing and destruction of habitat by elk.

By reintroducing Tasmanian devils into mainland Australia, can we possibly help restore ecological systems that support devils along with small to medium-sized native mammals?

Native and exotic predators

Tasmanian devils and

thylacines (Tasmanian tigers) were displaced across the mainland of Australia sometime after the

dingo was introduced from southeast Asia at least 3,500 years ago.

But these iconic Australian predators were still able to survive in Tasmania.

The island was created 10,000 years ago by rising sea levels, well before the arrival of dingoes on mainland Australia.

Dingoes have now been eradicated across much of mainland Australia, particularly within the seclusion zone of the

dingo fence in the southeast of the continent. The 5,400km fence stretches eastwards across South Australia into New South Wales and to southeast Queensland.

Exotic predators such as foxes and cats now thrive across many parts of Australia, and have

devastating impacts on small to medium-sized Australian mammals.

But until recently they have not been able to gain a foothold in Tasmania. Many ecologists believe the presence of the devil has prevented these other animals making their destructive mark on the ecology of Tasmania.

Sadly the situation is changing as a result of the

deadly devil facial tumour disease, an infectious cancer that has destroyed many populations of Tasmanian devils.

Estimates range up to 90% of some population groups now wiped out.

As a result,

feral cats are now moving into former devil habitats and hunting native species on Tasmania.

A fossil window to the past

So what does the fossil record tell us about the past life of the Tasmanian devil in mainland Australia?

The

Willandra Lakes World Heritage Area, in southeast Australia, provides an extraordinary archaeological and palaeoecological record of Ice Age Australia.

![]()

*This image is copyright of its original author

Recovery of fossils and devil coprolites from eroding bettong burrows at the Willandra Lakes World Heritage Area. Michael Westaway, Author provided

In the past, skeletal remains buried within the landscape were commonly fossilised. Evidence of small animals that dug burrows (such as burrowing bettongs) and the predators that pursued them in their burrows, are exceptionally well preserved.

Our excavations reveal how devils and other small-to-medium sized mammals and reptiles interacted over more than 20,000 years in this area. Even during the peak arid phase, known as the Last Glacial Maximum, it seems that devils and their prey successfully co-existed.

![]()

*This image is copyright of its original author

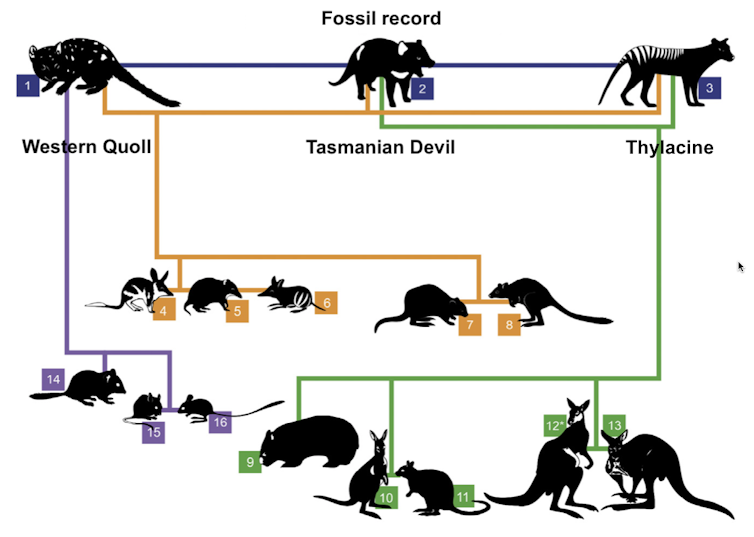

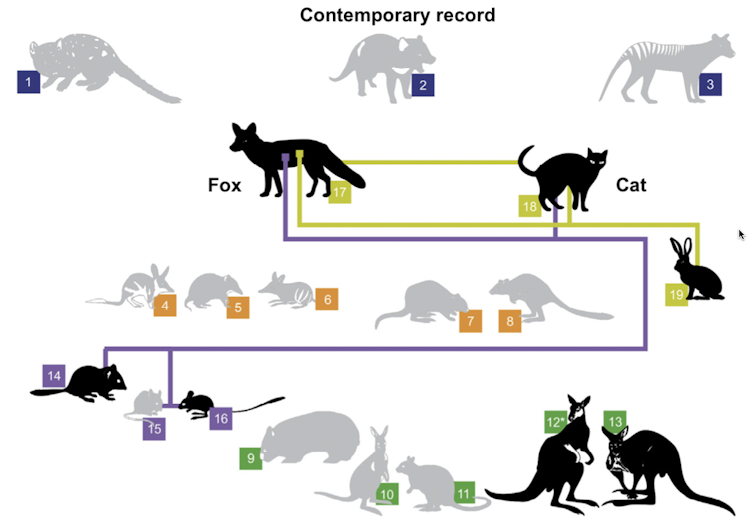

The fossil record (10,000 to 4,000 years ago): This shows the fauna reference condition prior to the arrival of the dingo. (1 Western Quoll, 2 Tasmanian Devil, 3 Thylacine, 4 Bilby, 5 Western Barred Bandicoot, 6 Southern Brown Bandicoot, 7 Burrowing Bettong, 8 Brush Tailed Bettong, 9 Wombat, 10 Nail-Tailed Wallaby, 11 Hare Wallaby, 12 Western and Eastern Grey Kangaroo, 13 Red Kangaroo, 14 Crest Tailed Mulgara, 15 Greater Stick Nest Rat, 16 Hopping Mouse, 17 Fox, 18 Cat, 19 Rabbit) Toot Toot Design, Author provided

![]()

*This image is copyright of its original author

The contemporary record: This shows today’s situation in the Willandra Lakes World Heritage Area. Light grey animals represent those animals that are now locally extinct. Toot Toot Design, Author provided

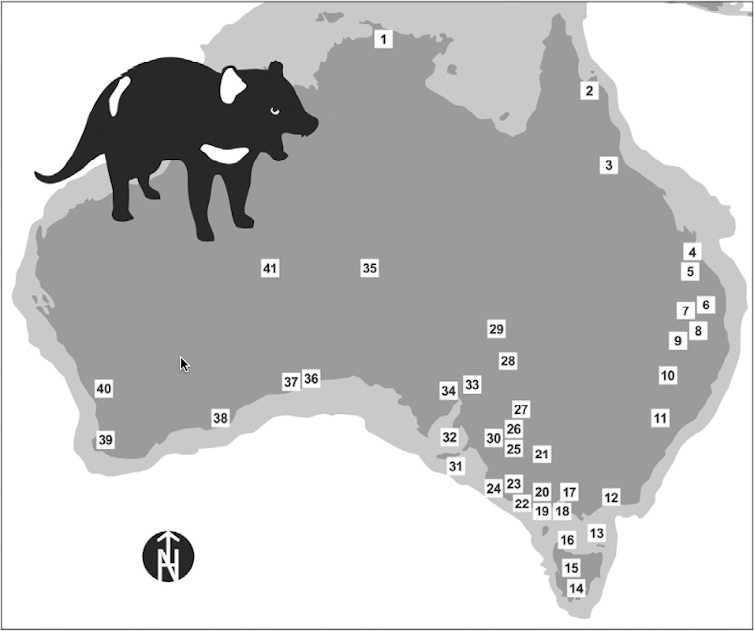

The fossil record shows that the range of habitats occupied by devils in the past was far more diverse than today, with populations being found across environments from the central arid core to the northern tropics.

This suggests that devils today should, theoretically, be able to reoccupy a similarly extensive range of habitats.

![]()

*This image is copyright of its original author

Former devil range across Australia as revealed by the known fossil record. Toot Toot Design, Author provided

Better the devil you know

Some ecologists suggest dingoes should be reintroduced into Australian habitats in order to reduce the impact of cats and foxes on native mammals.

One problem is that dingoes also prey on livestock. This is the reason the dingo fence was constructed during the 1880s.

But devils are not active predators of cattle and sheep. So reintroducing a predator that has a much longer evolutionary history with other native mammals in this country would likely receive far less opposition from pastoralists.

Read more: Deadly disease can 'hide' from a Tasmanian devil's immune system

A reintroduction of devils back to the mainland may be a new approach to consider for controlling the relentless, destructive march of exotic predators and restore crucial elements of Australia’s biodiversity.

It still needs to be demonstrated that devils can suppress the activities of cats and foxes on the mainland, as they seem to have done in Tasmania. Experiments with devils in a range of different settings would help to establish this.

A new research approach involving palaeontologists, conservation biologists and policy makers may help us understand how we can restore biodiversity function in Australia.

Source