+- WildFact (https://wildfact.com/forum)

+-- Forum: Nature & Conservation (https://wildfact.com/forum/forum-nature-conservation)

+--- Forum: Human & Nature (https://wildfact.com/forum/forum-human-nature)

+--- Thread: Making a difference (/topic-making-a-difference)

Making a difference - Rishi - 05-09-2017

*This image is copyright of its original author

Jobs That Allow You To Work With Nature

How to make the outdoors your office

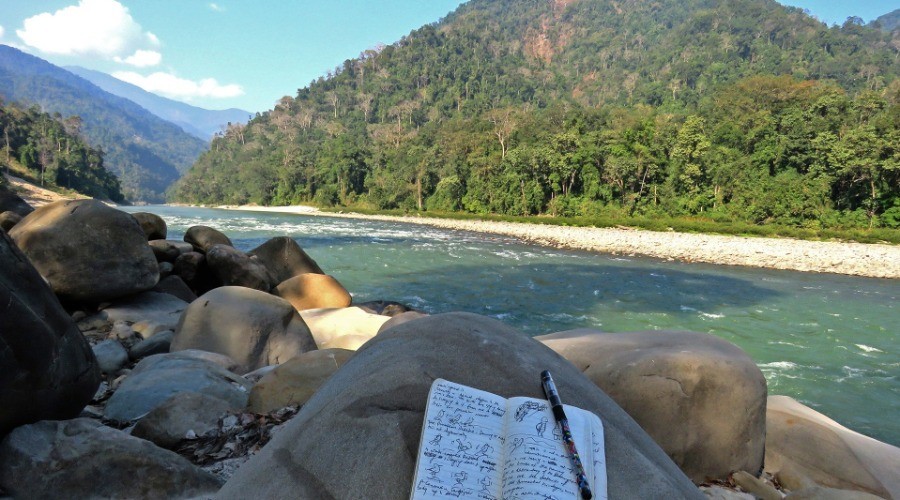

--- by Team NiFCareer paths that veer off the beaten track. Photograph: Rohan Chakravarty

*This image is copyright of its original author

Artist/Cartoonist

Rohan Chakravarty, Wildlife Cartoonist, Green Humour

The job: I convert information about biology and conservation issues into funny snippets in the form of comics, or present an animal or a place as a delightfully exaggerated caricature. Like scientists chase wild animals to gather droppings, I chase them to gather inspiration (and sometimes droppings too).

Sustainability: It depends on how crazy in the head you are. If work and play mean the same thing to you, this one's for you. It took a lot of rigour to make cartooning a career (not that the struggle is over yet). I held a day job as an animation designer for three years, before I could take up cartooning full time.

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

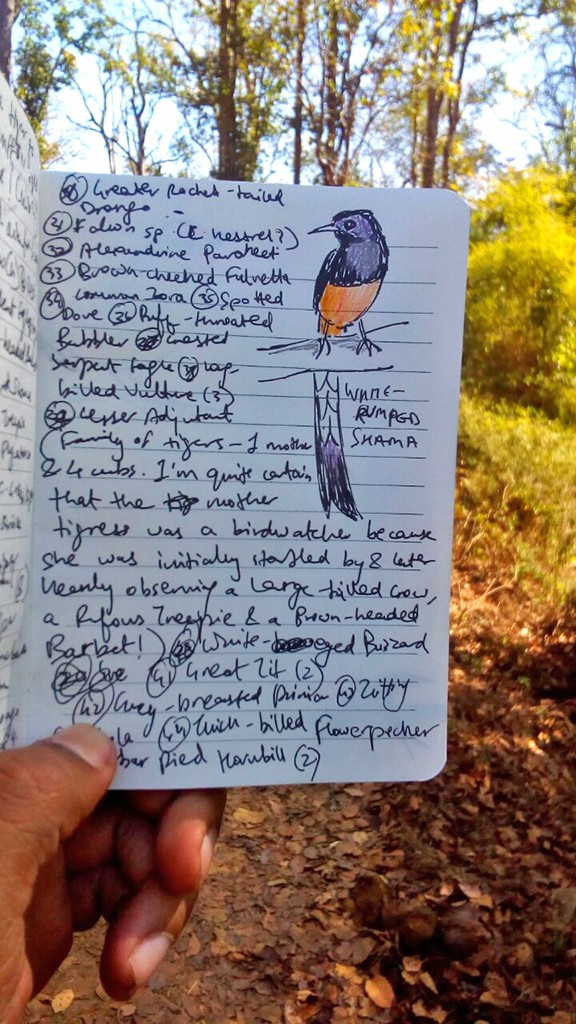

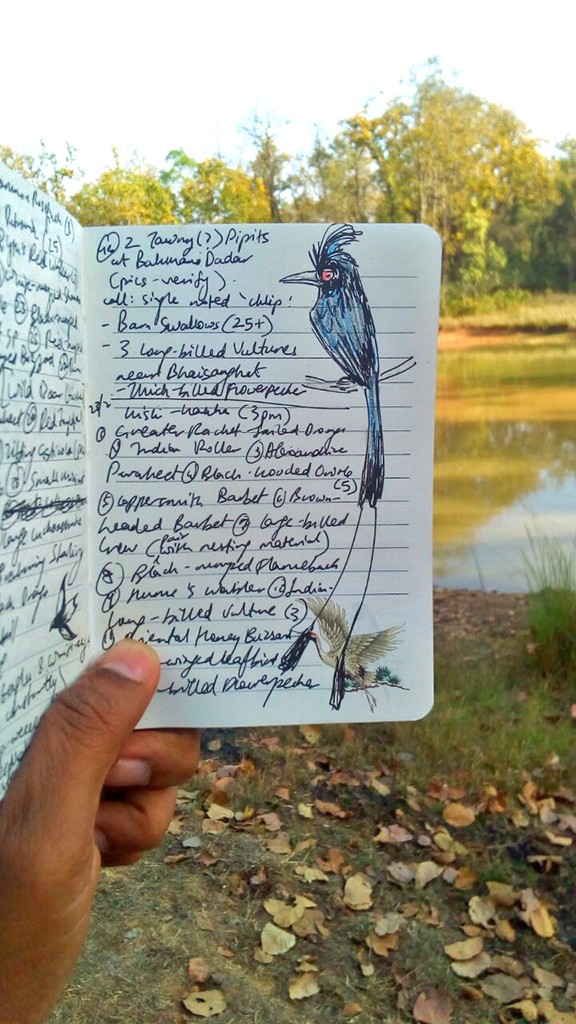

Quick sketches from the wild - the White-rumped Shama and the Greater Racket-tailed Drongo from Kanha. Photographs courtesy Rohan Chakravarty

The beginner's take home: Anything between ₹15,000 to ₹30,000. Now, with the Internet expanding like the belly of a Honeypot Ant, prospects are slowly turning sweeter. The more avenues you can tap into, the better the dough.

The takeaway: With social media, it's quite easy to get your work out to an audience, gain 'likes' and 'followers' and think you're a great cartoonist. But training is a lot more important than likes and followers. Stick figures are great means of expression, but they aren't cartoons. Watch animated classics, read the comic strip greats, study form, buy books on cartoon drawing (Christopher Hart is one of the best authors on these matters), focus on developing a style, draw hundreds of shapes, characters and expressions every day, write down ideas and doodle vigorously.

Filmmaker

Saravanakumar Salem, Wildlife Filmmaker/Cinematographer, Indian Wildlife Channel

The job: Depending on the assignment, I make wildlife films or sometimes just shoot them on behalf of a company. Making a film requires raising funds, coming up with a concept and then executing it.

Sustainability: As with any creative freelance work, this is very subjective. Hone your skills, keep getting better and you'll get more work. Your success depends on your performance.

*This image is copyright of its original author

A filmmaker's journey involves pathbreaking documentation of wildlife behaviour. Photograph courtesy Saravanakumar Salem, shot in Akole, Maharashtra for BBC - Leopards 21st Century Cats - Behind the Scenes.

The beginner's take home: The pay scale is variable. Nobody wants to pay you until you're good at what you do, and that takes time. Be ready to work for free or on a subsistence income until you get recognised.

The takeaway: Prepare for the long haul. This is not something that you can do well without a lot of effort. And you cannot rest on your laurels. Be consistently good. If you love the work and are willing to dedicate your time to it, you can make an impact in this field.

Fundraiser

Nishanth Ravindranathan, Fundraising Manager, Wildlife SOS

The job: To reach out to people and talk to them about wildlife conservation, and the work that we do at Wildlife SOS. I try and inspire them to support us in whichever way they can, through volunteering or donations. I work on grants and CSR objectives with companies to organise events. I also help conduct wildlife conservation awareness sessions at schools, colleges, and companies.

*This image is copyright of its original author

The role of a fundraiser can vary, from visiting corporate offices to creating awareness about their organisation. Photograph: Radha Rangarajan

The beginner's take home: It depends on your work experience in the NGO sector. I had none, so I joined as a tele-caller and earned ₹10,000 per month; starting pay is around ₹12,000 now.

The takeaway: The sooner you start and the more risks you are willing to take, the better. Your pay will probably be halved if you've moved from another industry. If you feel you can manage with that and are passionate about this work, jump right in. You won't regret it.

Indian Forest Service Officer

Vijay Mohan Raj, Chief Conservator of Forests, Belagavi Circle

The job: My team is responsible for the wellbeing of forests and wildlife in three districts of North Karnataka: Belagavi, Bagalkot and Vijayapura. This involves protecting forest land from encroachment, grazing, and illicit tree felling. We focus on soil and moisture conservation, wildlife protection, and man-animal conflict management. We commission studies on biodiversity documentation and manage forest resources for timber and fuelwood. We are also involved in creating public awareness through ecotourism.

Sustainability: The Indian Forest Service doesn't just provide a sustainable job, it's a journey of experiences. Most importantly, you work to preserve crucial natural resources, which ensures the sustainability of current and future generations also.

*This image is copyright of its original author

An IFS officer has access to pristine ecosystems, like Bhimgad Wildlife Sanctuary in the Western Ghats. Photograph courtesy Vijay Mohan Raj

The beginner's take home: A beginner would start off with around ₹60,000; senior officers make more than 2 lakhs per month. The perks and privileges are plenty - accommodation in heritage forest resthouses, a vehicle and dedicated support staff. An IFS officer has access to pristine ecosystems which are out of bounds for the common man, and gets to experience nature like no one else.

The takeaway: If you have a passion for the outdoors and adventure, the Indian Forest Service is for you.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Two tiger cubs caught in the headlights on a night patrol at BRT Tiger Reserve in Karnataka. Photograph: Vijay Mohan Raj.

Photography Tour Leader

Nisha Purushothaman, Co-Founder, Paws Trails

The job: To conduct wildlife photography tours, workshops and exhibitions. To spread awareness about conservation.

Sustainability: I work as a freelance consultant for web-related projects. My photography workshops help in covering the costs for trips I take to the forests.

The takeaway: There is no shortcut to nature/wildlife photography. Understanding animal behaviour is the key. Follow your dream. Life may not be easy, but a life spent living your dream is worth living.

Project Coordinator

Bhavna Menon, Project Coordinator, Last Wilderness Foundation

The job: To structure and execute field projects. I draw up proposals based on feasibility, and coordinate with concerned authorities and stakeholders.

Sustainability: Sustainability depends on the vision of a particular organisation. If the structure, vision and scale is clear, the model automatically becomes sustainable. Funding also plays a huge part in this, and that varies across organisations.

The beginner's take home: A starting salary could be anywhere between ₹15,000 to ₹20,000.

The takeaway: Read (lots!), ask questions, meet people working in the industry, volunteer with organisations. Field experience plays a pivotal role in helping you understand the nature of work you want to pursue - whether as a researcher, education officer, writer or otherwise.

Scientist/Teacher

Suresh Kumar, Scientist, Department of Endangered Species Management, Wildlife Institute of India

The job: To carry out field research on lesser-known and threatened fauna, primarily bird species across the Indian landscape. My research focuses on animal ecology, movement and migration studies, and conservation biology. I also train forestry officials and advise government departments on policy matters.

Sustainability: I completed my Master’s degree in Wildlife Science in 1997, but I only got this job ten years later. But now it is sustainable, since my position here is permanent.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Suresh Kumar shows students how to measure an elephant's footprints in Corbett National Park. Photograph: Radha Rangarajan

The beginner's take home: In the nineties, the starting stipend for a wildlife researcher or biologist was around ₹2,500. Now, it's ₹12,000, and if the candidate has cleared the required examinations (UGC-NET), then he or she gets a fellowship of around ₹25,000. To secure a permanent job, students should pursue a PhD in biological sciences.

The takeaway: This is an extremely exciting, challenging field of work. In recent years, the government, academic institutes, and NGOs have undertaken several wildlife research projects at the national and state level, which means there are lot more job opportunities today. Well-trained biologists are always in demand.

Veterinarian

Gowri Mallapur, former veterinarian at the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust

The job: To keep the animals healthy, and take measures to prevent disease. If an animal is sick, it should be treated in a way that causes it minimal stress.

The beginner's take home: Somewhere between ₹30,000 to ₹40,000. The job pays decently, but will never make you rich.

The takeaway: This work is satisfying on multiple levels - professional, personal and emotional. Being a vet is often "MacGyverish" - you need to think on your feet and no two days are alike. Financially, it can get frustrating, but these are always learning opportunities that propel growth. If you're passionate about wildlife care and an opportunity presents itself, just take it.

Travel And Documentary Photographer

Mayank Soni, Freelance Photographer

The job: To document vanishing cultures and shoot travel destinations for magazines. Besides this, I thoroughly enjoy shooting wildlife, though lately my focus has turned to communities (in conflict with wildlife), which have the potential to turn to conservation.

Sustainability: You have to juggle between assignments to stay afloat - the ones that pay well and those that are close to your heart. It will take around three to five years to get a stable income.

The beginner's take home: Freelance does not guarantee a fixed income, so anywhere between ₹10,000 to ₹30,000, depending on the assignments you do.

The takeaway: Work on a niche, long-term project, which you truly believe in. This will help you build a credible body of work.

Writer

Sejal Mehta, Writer/ Editor

The job: I write and edit across genres, and one of those genres deals with stories on nature. This involves finding stories about travel, conservation, communities and wildlife, and telling them in an engaging way to an audience that may well be unaware, or possibly uninterested in what is happening in our forests.

Sustainability: You start small but gradually make your way to a place that is comfortable. I have had a steady income right from the start of my career, so I've had no trouble.

*This image is copyright of its original author

A writer's job leads you to remote places and interesting stories. On a trek to the Living Root Bridges in Meghalaya. Photograph: Ashley Erasmus Lyngdoh

The beginner's take home: Depending on the media house, you'll make around ₹15,000 to ₹20,000 to begin with.

The takeaway: Work for organisations for a while before you start to freelance. This will help you understand all aspects of the publishing industry: writing, editing and advertising. When you start out, don't be content to sit at a desk and curate work, get out in the field, spend your own money if you need to, but travel to places that need to be written about, and meet people working at the grassroots. Be prepared to spend time reading. Get your facts right. Above all else, write endlessly to hone your craft. You have the power to tell stories to bring about change. Create awareness, educate, but also develop a style that entertains, and appeals to a larger audience.

We love a good critique but are infinitely partial to compliments. Both, roars and birdsong are welcome at [email protected]

RE: Making a difference. - Rishi - 05-12-2017

The legacy of Jadav Molai Payeng...

RE: Making a difference. - Rishi - 05-14-2017

AFFORESTT

This is a typical single-story tree plantation in Umatilla, Oregon, consisting of poplar trees planted with eight-foot spacing in order to force upward, knot-free growth.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Creating new forests where there were none before is the aim of afforestation. Degraded pasture and agricultural lands, or other lands corrupted from uses such as mining, are ripe for strategic planting of trees and perennial biomass.

Afforestation can take a variety of forms—from seeding dense plots of diverse indigenous species to introducing a single exotic as a plantation crop, such as the fast-growing Monterey pine, the most widely planted tree in the world. Whatever the structure, afforestation creates a carbon sink, drawing in and holding on to carbon and distributing it into the soil.

Plantations comprise the majority of afforestation projects and are on the rise globally, planting trees for timber and fiber and, increasingly, carbon offsets. Plantations are controversial because they are often created with purely economic motives and little regard for the long-term well-being of the land, environment, or surrounding communities.

To counter the ecological deserts of monoculture tree farms, Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki devised a completely different method of afforestation. His fast-growing, dense plots of native species show that afforestation can draw down carbon, while supporting biodiversity, addressing human needs for firewood, food, and medicine, and providing ecosystem services such as flood and drought protection.

Akira Miyawaki, a Japanese botanist and ecologist, has been planting forests along the coastline of Japan to protect it from Tsunamis and soil erosion.

Quote:Quoting Miyawaki, “The best forest management technique is no management at all. Just look after the saplings for a year or so and after that they are on their own. The fittest of them survive, just like they would in a natural forest.”

The miyawaki method of afforestation / planting trees involves the planting a number of different types of trees close together in a small pit. By closely planting many random trees close together in a small area enriches the green cover and reinforces the richness of the land. This will lead to co-existence of plants and as a matter of fact each plant draws from the other vital nutrients and they grow to become strong and healthy.

Shubhendu Sharma worked as an engineer for Toyota before he started Afforestt.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Shubhendu Sharma left his high paying job as an engineer to plant trees for the rest of his life. Using the unique Miyawaki methodology to grow saplings, Afforestt converts any land into a self-sustainable forest in a couple of years. He has successfully created 33 forests across India in two years. Here’s how he made it possible.

It all started when Sharma volunteered to assist a naturalist, Akira Miyawaki, to cultivate a forest at the Toyota plant where he worked. Miyawaki’s technique has managed to regenerate forests from Thailand to the Amazon, and Sharma thought to replicate the model in India.

Sharma started to experiment with the model and came up with an Indian version after slight modifications using soil amenders. His first tryst with making forests was in his own backyard in Uttarakhand, where he grew a lush green forest within a year’s time. This gave him confidence and he decided to launch it as a full-time initiative. He quit his job and spent almost a year to do research on the methodology.

Sharma, with an ONLY 1-year-old Miawaki Forest, Uttrakhand...

*This image is copyright of its original author

After much planning, research and enthusiasm, Sharma started Afforestt, an end-to-end service provider for creating natural, wild, maintenance-free, native forests in 2011.

Quote:“I realized it can’t be done as a ‘do gooder” activity. If I wanted it to succeed, I had to think it through and come up with a business plan, and a bunch of my friends helped me to set it up,” Sharma says.

Sharma, an Ashoka, TED and INK fellow was clear from the very beginning that Afforestt will be a for-profit organization. He wanted to change the industry and Afforestt was much more than just a business idea for him.

Quote:“The idea is to bring back the native forests. They are not only self-sustainable after a couple of years but also are maintenance-free,” Sharma says.

RE: Making a difference. - Rishi - 05-16-2017

This Delhi-based organisation has rescued, treated, and released over 1,500 wild animals

HEMA VAISHNAVI

Wildlife SOS has been providing sustainable alternative livelihoods to communities dependent on wildlife and natural resources, in addition to wildlife protection

One of the rehabilitated leopards the the WSOS Manikdoh Leopard Rescue Center

![]()

Wildlife SOS veterinarian Dr. Ajay feeding an orphaned leopard cub

Wildlife SOS has been providing sustainable alternative livelihoods to communities dependent on wildlife and natural resources, in addition to wildlife protection

One of the rehabilitated leopards the the WSOS Manikdoh Leopard Rescue Center

Wildlife in most parts of the world is under severe threat mostly due to different kinds of human activities, which have been destroying the natural habitat and endangering their lives through hunting and other illegal trading activities of wildlife products.

Wildlife SOS, a non-profit charity, is consistently working towards making a difference by helping conserve and protect the environment and wildlife.

Conserving nature and wildlife

Wildlife SOS was established in 1995 by Kartick Satyanarayan and Geeta Seshamani with the holistic belief that providing sustainable alternative livelihoods and education to communities dependent on wildlife and natural resources, would lead to sustainable wildlife protection.

Wildlife SOS, a non-profit charity, is consistently working towards making a difference by helping conserve and protect the environment and wildlife.

Conserving nature and wildlife

Wildlife SOS was established in 1995 by Kartick Satyanarayan and Geeta Seshamani with the holistic belief that providing sustainable alternative livelihoods and education to communities dependent on wildlife and natural resources, would lead to sustainable wildlife protection.

Kartick has been involved in wildlife conservation, animal welfare, and nature protection for over 23 years now. He is a member of the IUCN Bear Specialist Group (Sloth Bear Expert Team), the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (Advisory Board), Govt. of India (2007), and the Captive Elephant Evaluation Committee (Central Zoo Authority). He is a recipient of the prestigious Karamveer Puraskar (2009) and has been felicitated with the Indira Gandhi Paryavaran Puraskar Award, the inaugural Planman Media Award for Environmental Activism (2009)

An active senior wildlife conservationist and animal rights activist, Geeta has been involved with animal welfare and wildlife conservation for over 30 years now. In 1995, Geeta witnessed a sloth bear being forced to dance while its owner begged for money in Uttar Pradesh. She investigated the problem and later that year co-founded Wildlife SOS to rescue wildlife in distress, resolve man–animal conflicts, and educate the public about the need for habitat protection.

An active senior wildlife conservationist and animal rights activist, Geeta has been involved with animal welfare and wildlife conservation for over 30 years now. In 1995, Geeta witnessed a sloth bear being forced to dance while its owner begged for money in Uttar Pradesh. She investigated the problem and later that year co-founded Wildlife SOS to rescue wildlife in distress, resolve man–animal conflicts, and educate the public about the need for habitat protection.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Wildlife SOS veterinarian Dr. Ajay feeding an orphaned leopard cub

Today, the organisation has evolved to actively working towards protecting wildlife, conserving habitat, studying biodiversity, conducting research, and creating alternative and sustainable livelihoods for erstwhile poacher communities and communities that depend on wildlife for sustenance. Wildlife SOS started work on the rehabilitation of the Kalandar communities (originally Muslim gypsies with a highly nomadic lifestyle who were famous for their mastery over animals) through education and an alternative livelihood programme as an extension of this dancing bear rescue project.

“Be it changing the mindsets of people and fighting what was considered to be tradition to working with law enforcement authorities to facilitate various rescues and seizures, we have faced challenges on many levels. Also, caring for rescued animals is always a financial challenge as we are a non-profit organisation,” says a member of wildlife SOS.

“Be it changing the mindsets of people and fighting what was considered to be tradition to working with law enforcement authorities to facilitate various rescues and seizures, we have faced challenges on many levels. Also, caring for rescued animals is always a financial challenge as we are a non-profit organisation,” says a member of wildlife SOS.

Ending cruelty on animals

Wildlife SOS’s major project was the abolition of the barbaric practice of dancing bears in which sloth bear cubs were poached from the wild and trained using cruel methods to entertain tourists. As a part of Kartick and Geeta’s investigation into the illegal practice of dancing sloth bears, they embarked on an intensive research study from 1995 to 1997.

After presenting a report on this issue to the government of India, Wildlife SOS began the rescue of these dancing bears and established four rescue centers all over India and were able to take over 620 bears to these centres, where the bears were given medical care, nutritious diet, and freedom to roam in large natural enclosures.

![]()

Wildlife S.O.S co-founder Kartick Satyanarayan with a rescued sloth bear

![]()

A sloth bear at the Wildlife SOS Agra Bear Rescue Facility

![]()

Our rescued bears enjoying their structural enrichments

Wildlife SOS’s major project was the abolition of the barbaric practice of dancing bears in which sloth bear cubs were poached from the wild and trained using cruel methods to entertain tourists. As a part of Kartick and Geeta’s investigation into the illegal practice of dancing sloth bears, they embarked on an intensive research study from 1995 to 1997.

After presenting a report on this issue to the government of India, Wildlife SOS began the rescue of these dancing bears and established four rescue centers all over India and were able to take over 620 bears to these centres, where the bears were given medical care, nutritious diet, and freedom to roam in large natural enclosures.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Wildlife S.O.S co-founder Kartick Satyanarayan with a rescued sloth bear

In 2009, Wildlife SOS made history by bringing an end to the ‘dancing bear’ practice that inflicted terrible cruelty on thousands of highly endangered sloth bears, by taking the last dancing bears off the streets of India. In turn, the organisation has rehabilitated, sponsored education, and provided alternative livelihoods for the Kalandar communities, who for centuries were dependent on sloth bears to earn a living.

Wildlife SOS has also been focusing on the plight of captive elephants in India which are privately owned and have the cruel history of being used for begging, held in temples for ‘blessings to temple visitors’, and forced to perform in circuses.

The organisation is trying to improve the situation for these elephants by rescuing injured and sick elephants that are forced to work in oppressive conditions as well as doing advocacy and using legislation to prevent the capture and trading of wild elephant calves and their sale and trade in private ownership as that will go a long way to resolving the abuse of privately owned elephants.

“We also work with Asiatic Black Bears and Leopards, two species that are in intense wild animal–human conflict situations in India, particularly in the states of Jammu & Kashmir with black bears and leopards, and with leopards in Maharashtra,” says a member of wildlife SOS.

Awareness initiatives

Wildlife SOS has been conducting awareness programmes to educate the public and encourage responsible community participation in conservation initiatives such as tree plantation drives in association with the school authorities of Jammu & Kashmir, cleaning plastics from Bannerghatta to cleaning the Dal Lake with schools and colleges.

Students and volunteers learn about animal conservation and behaviour and going forward these students will organise rallies to grow awareness about wildlife conservation and protection amongst their communities.

Wildlife SOS has also been focusing on the plight of captive elephants in India which are privately owned and have the cruel history of being used for begging, held in temples for ‘blessings to temple visitors’, and forced to perform in circuses.

The organisation is trying to improve the situation for these elephants by rescuing injured and sick elephants that are forced to work in oppressive conditions as well as doing advocacy and using legislation to prevent the capture and trading of wild elephant calves and their sale and trade in private ownership as that will go a long way to resolving the abuse of privately owned elephants.

“We also work with Asiatic Black Bears and Leopards, two species that are in intense wild animal–human conflict situations in India, particularly in the states of Jammu & Kashmir with black bears and leopards, and with leopards in Maharashtra,” says a member of wildlife SOS.

Awareness initiatives

Wildlife SOS has been conducting awareness programmes to educate the public and encourage responsible community participation in conservation initiatives such as tree plantation drives in association with the school authorities of Jammu & Kashmir, cleaning plastics from Bannerghatta to cleaning the Dal Lake with schools and colleges.

Students and volunteers learn about animal conservation and behaviour and going forward these students will organise rallies to grow awareness about wildlife conservation and protection amongst their communities.

*This image is copyright of its original author

A sloth bear at the Wildlife SOS Agra Bear Rescue Facility

Wildlife SOS is also known for holding exhibitions and stalls to spread awareness about wildlife conservation among the masses as well as working with local communities and stakeholders educating and empowering them to patrol and protect their forests. Workshops are held regularly with Law officers, Forest Department Enforcement Officers, Police and Customs officers to educate them about wildlife trade, recognition of contraband, simple knowledge of law in the fields, conflict management, and rescue techniques in order to mitigate animal–human conflict.

Impact

Currently, Wildlife SOS is providing lifetime care for 24 rescued elephants at their centres in Mathura and Haryana, over 300 sloth bears across their centres, six Himalayan black bears in Jammu & Kashmir, and 34 leopards in Maharashtra. Moreover, more than 1,500 wild animals are rescued, treated, and released by the rescue teams across the various centers annually.

“As part of our Kalandar Rehabilitation Programme, over 3,500 families spread out across four states and over 15 villages have received support to become economically self-sufficient over a period of 12 years. Additionally, we have supported the education of over 1,360 Kalandar children and 1,500 Kalandar women have been given vocational training or seed funding to start their own businesses,” says a staff member.

Wildlife SOS operates 11 wildlife rehabilitation facilities across India.

Impact

Currently, Wildlife SOS is providing lifetime care for 24 rescued elephants at their centres in Mathura and Haryana, over 300 sloth bears across their centres, six Himalayan black bears in Jammu & Kashmir, and 34 leopards in Maharashtra. Moreover, more than 1,500 wild animals are rescued, treated, and released by the rescue teams across the various centers annually.

“As part of our Kalandar Rehabilitation Programme, over 3,500 families spread out across four states and over 15 villages have received support to become economically self-sufficient over a period of 12 years. Additionally, we have supported the education of over 1,360 Kalandar children and 1,500 Kalandar women have been given vocational training or seed funding to start their own businesses,” says a staff member.

Wildlife SOS operates 11 wildlife rehabilitation facilities across India.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Our rescued bears enjoying their structural enrichments

Their upcoming projects include the establishment of an elephant hospital, expansion of the elephant conservation and care centers, human–wildlife conflict mitigation, wildlife research and forest restoration projects.

“India’s forests and wildlife are currently under great pressure and it is Wildlife SOS’ privilege to dedicate our efforts towards the protection of some of the leading species such as sloth bears, elephants, and leopards. We also cross over from conservation to welfare because we believe both ex-situ and in-situ conservation is closely linked. Therefore, our work involves running wildlife rescue and rehabilitation centres as well as regeneration of forests and putting measures into place that help conserve wildlife in their natural habitat,” says Geeta.

“India’s forests and wildlife are currently under great pressure and it is Wildlife SOS’ privilege to dedicate our efforts towards the protection of some of the leading species such as sloth bears, elephants, and leopards. We also cross over from conservation to welfare because we believe both ex-situ and in-situ conservation is closely linked. Therefore, our work involves running wildlife rescue and rehabilitation centres as well as regeneration of forests and putting measures into place that help conserve wildlife in their natural habitat,” says Geeta.

RE: Making a difference. - Rishi - 05-17-2017

The Ice-man of India...81-year-old retired civil engineer from Ladakh has built 12 artificial glaciers to fight global warming.

Chewang Norphel was born to a middle-class family in Leh, Ladakh. After completing a diploma course in civil engineering from Lucknow, Chewang worked for the rural development department of Jammu and Kashmir for 35 years, before he ‘officially’ retired in 1995. His work, however, continues even today.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Image : Vimeo“There is scarcely a village in Ladakh where I have not made a road, a culvert, a bridge, a building or an irrigation system,” Chewang told Rain Water Harvesting. What makes his efforts in rural development awe-inspiring is his ingenious approach to solving the water problem in the area.

“I realised that all the problems in the region were related to water. In most areas, it was scarce. In others, it was being wasted,” he says. Villagers, who relied primarily on agriculture, couldn’t get water during the spring season. During summer, when the glaciers higher up in the Himalayas melted and water could reach the area, the soil had become dry.

Climate change and global warming made things worse. Water shortage led to the rural folks leaving for cities in search of jobs, further destroying the rural economies and the communities that tightly held people together in the scarcely populated region of Ladakh.

While looking for solutions, Chewang, in 1987, spotted how a small stream of water had frozen solid under the shade of a group of poplar trees. The stream flowed normally elsewhere in the area. Chewang realised that slowing down a stream can help divert it into valleys, which will stay frozen for longer seasons of the year, thereby creating an artificial glacier.

“The best way to deal with this (water shortage) is the construction of clean, efficient channels. I noticed in Leh that water did not freeze in the channels, but did so in the thin iron pipes. As the pipes are made of metal and are very thin, they lose heat quite rapidly,” he told Point Blank 7.

Work began immediately, and continues till date. Chewang and his volunteers have built 12 artificial glaciers in the region, which have significantly recharged groundwater in the area, and are providing water to remote villages for irrigation.

The the length of these glaciers vary from 500 feet to 2 km, and they serve over 100 villages in the region. Chewang, who won the Padma Shri in 2015, and is dearly known as ‘ice man’ or ‘glacier man’, knows the fight is far from over. In order to continue his efforts to fight the problem of water shortage, Chewang has also made CDs that will help younger generations build their own glaciers.

RE: Making a difference. - Spalea - 05-17-2017

@Rishi :

About#5: Big man ! Admirable.

RE: Making a difference. - Rishi - 05-18-2017

(05-17-2017, 09:10 AM)Spalea Wrote: @Rishi :

About#5: Big man ! Admirable.

More to come..keep following...

RE: Making a difference. - Rishi - 05-18-2017

WILDLIFE ACTIVIST SANJAY GUBBI WINS GREEN OSCARS

*This image is copyright of its original author

Sanjay Gubbi

Karnataka’s famed wildlife activist Sanjay Gubbi won the annual Whitley Awards, dubbed as the ‘Green Oscars’, for his work to protect Karnataka’s tiger corridors. Gubbi, received 35,000 pounds (USD 45,374) prize money for the projects.

Gubbi had quit his job as an electrical engineer to work with nature and wildlife. In 2012, working closely with the Karnataka government, he secured the largest expansion of protected areas for the conservation of tigers in his state. “Karnataka is home to the highest number of tigers in India, and in 2015. Our aim is to take the numbers up to 100 over the next few years. This can only be possible through thorough participation of the community,” he said.

Gubbi, 45, a conservation biologist with the Mysuru-based Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF), now holds a Master's Degree in Conservation Biology from University of Kent, UK where he received the Maurice Swingland Award for the best postgraduate student of the year. His dissertation from the M.Sc won two major international awards. He is the recipient of Carl Zeiss Wildlife Conservation Award for 2011.

He came up with the first tiger corridor initiative work carried out in the entire world.

Since 2010, Gubbi and his team have helped secure 2,385 sq. km for wildlife protection, an area almost three and a half times that of Bengaluru. Over five years, Gubbi helped create what he says is India’s largest contiguous landscape for tigers (around 9,500 sq. km, including 7,038.2 sq. km of protected area and 2,500 sq. km of reserve forest area) by connecting 23 discrete protected areas (PAs; tiger reserves, national parks, wildlife sanctuaries) through corridors and new sanctuaries. It is the largest expansion of conserved landscapes India has seen since the 1970s. Today, Karnataka has three large protected area complexes, which extend from the Bhimgad-Anshi complex that borders Goa in the west to the Nagarhole-Bannerghatta complex in the south, bordering Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

The areas selected are low on human population with little disturbance from the urban areas. They are mostly forested land.

*This image is copyright of its original author

To do this, one needs to navigate a more fraught landscape, one that is interwoven with basic human needs, political aspirations and profitable futures, none of which a tiger can offer. “Wildlife conservation is the hardest sell. How do you market an elephant, an otter or a frog?”, asks Gubbi.And so, over 2010-11, Gubbi and his team set about the jungles of Karnataka to find real estate for wildlife—decent forest patches that were still categorized as reserve forests. Gubbi’s interest in such areas goes back to 2002, when he was tramping through the forests around the Dandeli and Anshi national parks in northern Karnataka. His mapping showed that there was good potential for large mammal conservation, and he decided to propose that the reserve forests be declared as sanctuaries. The first expansion of this landscape resulted in the Bhimgad-Anshi complex that now connects nine protected areas. “We lobbied with the government, pushed the file from 2002-05. Seven years later, it was finally declared (a sanctuary) in 2009,” says Gubbi.

Gubbi, along with H.C. Poornesha, a GIS (geographic information system) expert, and his team looked for areas with high tree cover and no human settlements. Human habitations were left alone in enclosures, a more socially acceptable alternative because of restrictions on human activity inside PAs. Of the 4,700 sq. km that was identified, 2,385 sq. km is protected today. “These forest areas were threatened by encroachers and politicians. These habitats would have deteriorated as our misdeeds have gone on eliminating the tiger, but now they can grow into better habitat,” says B.K. Singh, a former principal chief conservator of forests (wildlife) for Karnataka.

This was all possible due to the joint efforts between Gubbi’s team and the Government. “One person I especially have to thank for the success of this mission is Poornesha H.C. and his excellent skills in Geographical Information System (GIS), which were critical in our work on protected area expansion,” says Gubbi.

It wasn’t an easy task giving shape to this unique project. Convincing political leaders and the government was difficult.

Quote:“Of course, they asked what’s in it for people here? What will they get out of it? So we explained to them the advantages in that context,” says Gubbi.

The team explained to the Government that there would be an increase in tourism, flood control, better air quality and many more such benefits by expanding the protected areas. The Government, seeing the larger benefit, agreed to the idea and supported the initiative.

By now, Gubbi has spent as much time in political corridors as he has finding corridors for wildlife. When we met in November in Delhi, he had said: “I am here to meet lawyers, wait for people and make hundreds of phone calls to get one appointment. It is frustrating and horrible but you have to do it."

“Most of the time in science, you build your data first—there are tigers here, so you declare it as PA. But here, we did it the other way around. We first looked at social acceptance and political viability rather than ecological quality,” says Gubbi.

The seven years it took to declare Dandeli-Anshi a wildlife sanctuary/protected area taught Gubbi an important lesson, “You have to follow your file from table to table and see it off to the last mile.” A PA declaration is a complex juggling operation involving bureaucrats, local politicians, the state government and forest department—a tangle of egos, political compulsions and vested interests.

Another of the success stories of Gubbi’s work is in Malai Mahadeshwara Hills (906 sq km) that was declared as a new wildlife sanctuary in May 2013 due to his team’s efforts. They now have camera traps in that area and have seen fantastic results for tigers.

The tale of how MM Hills got declared as a sanctuary is nothing short of dramatic. Around the time of the May 2013 Karnataka state election, it was feared that vested interests in quarrying might be able to use the situation to their advantage—if they did, it would be difficult to preserve the landscape of MM Hills. The new PA, then, was declared ahead of the assembly election. “We were lucky it went unnoticed. It was done practically between governments,” says Singh, laughing.

Changing others’ minds is sometimes about forgetting your own objective completely. “With politicians, I didn’t talk about science or tigers,” says Gubbi. “I talked about water.”

And C.P. Yogeshwar, a former state minister of forests and a five-time MLA from Channapatna, a water-stressed taluka (administrative division), listened. One of his long-term projects was to recharge the groundwater, filling 150 dry tanks in the taluka by lifting water from the Cauvery. “It was the only way to improve irrigation in my area, to develop economically. I got the connection between protecting nature, forests, water and farmers,” says Yogeshwar. Today, he claims, these tanks irrigate 75% of the taluka.

Today, forest watchers and guards rush to Gubbi with their problems. Most of the ground-level staff consists of local tribals desperate for some extra employment. At the Holemuridahatti (“where the river takes a sharp turn”) camp, water is scarce. It has to be carried up manually from the river because there is no power here, so Gubbi is mulling over setting up a small solar pump.

Staff recruitment, retention and motivation are critical to the kind of protection a park gets. “Medical and life insurance, direct debit of salary into accounts, we need all these interventions,” he says.

Sanjay’s recent work, focusing on the Western Ghats of Karnataka, India has strived to reduce the impact of habitat fragmentation, collaborated with the Karnataka Forest Department towards an expansion of protected areas, helped institute new social security and welfare measures for forest watchers and guards. On these projects, Sanjay works with a wide cross-section of people, including policy makers, media and social leaders.

Sanjay also conducts training workshops for print and electronic media and conservation enthusiasts, among others, to expand support for and enhance public understanding of conservation. He has taught Master’s program courses at the National Centre for Biological Sciences and the Wildlife Institute of India. Today, Sanjay sits on the State Wildlife Board and other key panels of the state.

He writes extensively both in English and Kannada, and is especially keen on popularising wildlife conservation in local languages.

With his award money, Gubbi hopes to reduce deforestation in two important wildlife sanctuaries which connect several protected areas and act as corridors for tigers, allowing them to move between territories.

RE: Making a difference. - Rishi - 05-24-2017

Individual efforts matter...

*This image is copyright of its original author

RE: Making a difference. - Rishi - 05-27-2017

RE: Making a difference. - Rishi - 07-11-2017

*This image is copyright of its original author

Abhishek Ray, a celebrated Bollywood music composer, is also a certified tiger and leopard tracker, a conservationist, and wildlife activist. He bought a hill, adjacent to the Corbett National Park, and turned it into the Sitabani Wildlife Reserve. Here’s how he did it.

Indian music composer Abhishek Ray takes music seriously, but not as seriously as he takes wildlife. "The forest has its own sounds and those are the best that I have heard," he says. "I do not understand why man has to monopolise land and water resources in the forest. The number of resorts around the Kosi River at Corbett Tiger Reserve has gone up by great numbers. The first thing that these resorts do is sanitise the grounds and make it animal-proof and then they capture the water banks and make it exclusive to humans. They live off the wildlife as yet, they leave no room for wildlife to survive!"

A successful music composer in Mumbai, Abhishek Ray has been volunteering as a tracker for tigers and leopards for the Indian government since the age of 12. "My job took me to many remote areas and as I grew older I wanted to invest in a forest. I kept scouting for opportunities to invest in wasted agricultural lands," says Abhishek. "I found this land about ten years ago. There is a lot of hoof animal activity on it and this had degraded over years. I loved this land from the moment I set eyes upon it. It is right next to the forested area and is part of the tiger corridor with one side of a hill. I had no human neighbours to trouble the animals who would come to this land after regeneration."

Ray invested all his life's saving in buying the land from the families of the villages. Seven years and several greatly detailed plans later, the forest seems to have taken on life with a name - Sitabani.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Abhishek Ray is known throughout Bollywood as the music director of films such as Paan Singh Tomar, Saheb Biwi Aur Gangster, and Welcome Back. But he is also a certified tiger and leopard tracker, a conservationist, and wildlife activist.

An animal lover since childhood, Ray recollects that he would feel sad when he saw animals in cages at the zoo. He grew up aching to see animals reclaiming their habitats and walking free.

As an adult he became aware that humans were driving wild animals to extinction by taking over their land. “So I decided to invest whatever savings I had in a land where wild creatures could roam free – to return this habitat to its original inhabitants."

Being naturally attracted to big cats, he learnt how to read the sights and sounds of the wild from Dr G. V. Reddy at Ranthambore National Park. “As you start priming your senses, the forest opens up like a hidden book and starts giving you clues. Read the clues and you start getting a whiff of the most elusive creatures of this planet and their enigmatic, secretive lifestyles," he says.

Calling it an addiction, Ray began to volunteer in big cat census activities in various parts of India.

*This image is copyright of its original author

A tiger hidden among the grass at Sitabani Wildlife Reserve

It was during one of these tracking expeditions in the Corbett landscape that he came upon a large hill. Barren and lifeless since the villagers around the mountain had used up all its trees and resources, Ray observed how the setting was perfect. Surrounded by sal tree forests, it had a stream that cut across a cliff. Frequented by deer, and therefore tigers and leopards, the land that became the reserve was just waiting to be found by Ray.

When he made his name in Bollywood, with five hits as a composer in award-winning films, he was finally able to put all his energy into making his dream come true. He went ahead and bought the land that he had earmarked for his reserve. “My family and friends were enthusiastic and supportive, though I was not investing in a typical, safe investment like a builder’s posh flat in Delhi or Mumbai,” he says.

Soon after acquiring the land, he set about developing a water body in it.

*This image is copyright of its original author

It worked as a magnet, attracting wildlife to quench their thirst. He set up a natural rainwater harvesting system, ensuring that there was a long lasting supply of water. Simultaneously, he sowed seeds for healthy grass and got rid of the weeds. He developed one part of the land into open grassland, and planted endemic trees (such as ficus, banyan, jamun, and wild mangoes, among others) on the slopes. “The land, which had been abused by years of slash and burn techniques, sprang back to life and wildlife gradually followed,” he says.

"There is a temple in these parts called Sitabani Temple and the locals believe that Sita spent some years here after leaving Ram to raise her sons, Luv and Kush. I loved the story and decided to name the forest after it. I like phonetically pleasant names like the poet Gulzar with whom I had worked some years ago," he shares. "The first thing I did was to make sure villagers and their cattle did not use the land in a manner as unsustainable as they had been doing. I also know that water is a magnet for life and developed a man-made perennial water body in the reserve. It was a matter of months but all the animals in the forest came to know that this reserve had a reliable water source where they would not be threatened. Soon, the man-made lake took on the form of a natural pond because of the bamboos I had planted around it, and became a haunt for all the animals,"he shares. "The next step was to rid the land of a plant parasite called Lantenna. It is very difficult to get rid of it as you have to cut it, hang it inverted for some months for it to dry out completely and then burn it. If any of the steps is not complete then the parasite returns to kill all other forms of plants or grass that tries to grow. When I finally succeeded, I planted several varieties of grass and endemic fruit plants like amaltas, sycus, jackfruit, mango and in the drier portions, jamun - which helps in increasing moisture in the soil."

Today, with more than 600 kinds of rare birds and a long list of wild animals, the habitat is free from the devastating touch of humans.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Chestnut Bellied Nuthatch at the reserve

His consistent efforts over seven years have helped give a new lease of life to the land with big cats, deer, monkeys and over 600 species of birds visiting his reserve. "Do you have pen and paper at hand because the list of rare sightings is a long one," he laughs. The Indian Pita, Forest Owlet, Asian Bard Owlet, Brown Fishing Owl, Grey Hooded Warbler, Crest-Serpent Eagle, Steppy Eagle, Changeable Hawk Eagle, Long Legged Buzzard apart from many kinds of Flycatchers, Bee eaters, Woodpeckers and Orioles, are among the frequent visitors to the reserve today.

At an altitude of 1000 metres, the sal forest overlaps with an oak forest, which attracts Himalayan and plain land birds. Rare sightings include striped hyenas, leopard cats, otters, and civets.

*This image is copyright of its original author

The Sitabani Wildlife Reserve is part grassland, part forest.

The estate has Kumaoni style stone cottages located at strategic points, with a view of the tigers. They serve country food and Himalayan mineral water. But that’s where the comforts stop. The wildlife reserve gives first priority to the needs of the animals, not humans.

He also talks to the people in the surrounding villages about the importance of maintaining an ecosystem. “For most of them wildlife is just free meat or a nuisance. I try to make them understand that the right numbers of tigers and leopards in the forest keep the population of monkeys, langurs and wild boar at bay. So these wild cats, in turn, protect the farmers’ crops.”

The painful process of regeneration of the Sitabani Reserve is nearly complete and Abhishek Ray is quite clear that he does not plan to open the gates to everyone. "I don't mind genuine birdwatchers and nature-lovers to experience Sitabani but there will be no loud music and bright lights here," he says. "I do make money being a music composer in Mumbai but I would also like to invest in tourism at Sitabani by extending an honest experience with nature. There is no wi-fi or television here. This is the land shared by humans and animals and humans will have to adjust to the jungle, not vice versa."

The big cats have also been visiting, some quite regularly

*This image is copyright of its original author

Pic Courtesy: ABHISHEK RAY

"When the forest regenerated and the animals started to visit the water body regularly. I would hear the mating calls of two tigers in two corners of the forest. With the passage of time they would move closer, and then they finally stopped when they found each other," he shares.

When Abhishek started setting up bamboo homes for the birds, they in turn showed him the use of a local cotton flax that they used to make their nests warmer.

Abhishek shares a special bond with a resident tigress who has displayed complete trust in him, a matter of great pride for the musician.

*This image is copyright of its original author

A few years ago, as music composer Abhishek Ray strolled through his estate, he stopped dead in his tracks when he came across a tigress. She was lying in the grass, bathing in the moonlight. As he approached, she looked at him sceptically, but then lay back down. Ray had the rare opportunity to take photographs. “After half an hour went by, she casually turned around and showed me her back,” he recalls. “No wild animal would ever drop its guard completely in front of a human at night and turn its back to him unless that animal has implicit trust in the human,” he says.

For Ray, who bought a hill and converted it into a wildlife reserve estate, this was the moment when he realised all his efforts so far had paid off. “This moment gave me the power and belief that lets me fight many hindrances that life throws my way,” he adds.

RE: Making a difference. - Polar - 07-17-2017

A good and very much needed thread!

Even though I am studying Construction Engineering (a bit ironic), I can also use this credential to make nature reserves in the future if I get a big enough public following, great-sized territories, and possibly the help of some of you guys if any of you are willing!

But that'll be in the far future (more than a decade later).

RE: Making a difference. - sanjay - 08-18-2017

This Family Did Not Send Their Children to School, but Taught Them by Creating a Forest

Thirty-six years ago, Gopalakrishnan and Vijayalekshmi decided that their yet-to-be-born son will not go to school. As government school teachers, they were themselves disillusioned with the limitations of formal education and how it left children unprepared to deal with life.

They dreamt of a school environment that is close to reality- open, democratic and with fluid boundaries.

Read a heart touching story of man loving nature

http://www.thebetterindia.com/112174/sarang-hills-alternate-school-sustainable-living/

RE: Making a difference. - Polar - 08-19-2017

@sanjay,

Active and natural education is a great thing! Not only does it teach children good survival skills and natural habitation, it also rids many attention and mental conditions such as ADD, ADHD, depression (at least situational), anxiety, and many more! No wonder people in inside environments feel a little "empty" inside...

RE: Making a difference. - Polar - 10-22-2017

Hey members, I have just released the short clip of me sharing WildFact through my YouTube channel!

Tell me what you think of it and if this is good enough, then I will attach this clip to the end of my videos in the future!