+- WildFact (https://wildfact.com/forum)

+-- Forum: General Section (https://wildfact.com/forum/forum-general-section)

+--- Forum: Debate and Discussion about Wild Animals (https://wildfact.com/forum/forum-debate-and-discussion-about-wild-animals)

+--- Thread: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting (/topic-a-discussion-on-the-ethics-and-practical-function-of-hunting)

A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - Sully - 12-02-2019

In this thread I want to know your opinions on hunting. Is it ethically correct? Is it practically correct (e.g population control)? Should we only hunt to eat? Should we hunt "problem" animals (not necessarily man eaters)? Is trophy hunting justifiable due to the money it brings in for conservation? Are blood sports like fox hunting fine if the population is sustained? And many more variations of the complexities the issue of hunting brings. I'm sure we all have a nuanced view we've developed on this topic over the years, and I'd like to know where everyone stands.

RE: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - Sully - 01-29-2020

A Philosophical Critique of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation

*This image is copyright of its original author

Kirk Robinson2 days ago

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Bighorn in Rio Grande Gorge © John Miles

Featured image: Bighorn sheep © John Miles

By Kirk Robinson

Abstract: I start from the recognition that wildlife management is an evolving practice, not something permanently fixed in a set of unalterable tenets. Among other things, I present and argue for a reformulation of tenets of the NAM that will result in a more consistent and coherent set of ideas that, if put into practice, will result in wildlife governance that is more democratic, more ethical, better scientifically grounded, and that better promotes wildlife conservation. The key is the elimination of trophy hunting. One of the tenets of the NAM is #2: Elimination of markets for game. This prevents a repetition of tragedies such as were inflicted on the American bison and the passenger pigeon. The next big step should be the elimination of trophy hunting, which, as it happens, is also a kind of market for game. KR

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation (NAM), first published in 2001, was written by three white male hunter-biologists: Valerius Geist, Shane Mahoney and John Organ. It consists of seven principles or tenets which the authors claim have guided wildlife management in North America since early in the 20th century and are the bedrock of wildlife conservation. State wildlife management agencies and sportsmen’s organizations now enthusiastically tout the NAM as both guiding and justifying what they do.

I want to look into this, with a focus on three of the seven principles. These principles are fundamentally prescriptive. They purport to state how wildlife management ought to be conducted to best promote conservation. My aim is to get clear about the prescriptive content of these principles and to evaluate this claim. I shall not address here the grossly overblown view that wildlife management through hunting accounts for virtually all wildlife conservation in North America—a view that has been exploded by numerous critics.

#1. Wildlife is a public trust resource.

#4. Wildlife may be killed only for a legitimate purpose.

#6. Science is the proper tool for discharging wildlife policy.

#1: “Wildlife is a public trust resource.” At first glance this looks like an explicitly descriptive statement owing to the copula is. But surely it is meant to have prescriptive force, viz: Wildlife is to be (= ought to be) managed as a trust for the benefit of the beneficiaries—in this case, all citizens in perpetuity. #1 implies that wildlife conservation is imperative.

#1 also identifies wildlife as a resource, as if, like minerals, wild animals are to be used for the benefit of human beings but possess little or no independent value. This way of valuing wildlife, which I shall refer to as resourcism, is the heart and soul of the NAM. It underlies the idea that hunting is an essential tool, and perhaps the only really necessary one besides habitat protection, for promoting wildlife conservation.

These two ideas—wildlife as a public trust and wildlife as a resource—are not incompatible. At one extreme there are people who value wildlife strictly as a resource and who believe the proper goal of management is to provide for sustainable exploitation of the resource with a minimum of constraints. At the far other end of the spectrum are people who believe that wildlife possesses such great intrinsic value that it should not be exploited at all. I shall refer to this way of valuing wildlife as protectionism. Between the two extremes are people who believe appropriate constraints will allow for exploitation of the resource while also protecting it.

Within this broad class of people, I distinguish between those who value wildlife (including ecosystems and the land generally) primarily as a resource and those who value it primarily for its intrinsic value. One value is prioritized over the other. If one is thinking in terms of means and ends, the one group values wild animals primarily as a means, while the other group values them primarily as ends in themselves (to use Kantian terminology).

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Three Rivers NM Petroglyph © Kirk Robinson

Wildlife management agencies use the inapt terms “consumptive user” and “non-consumptive user” to cover what is in reality a wide range of differences in how people value wildlife. Obviously, a person can be a hunter and also enjoy watching wildlife—can be both a consumptive user and a non-consumptive user. Recently, social scientists coined the more nuanced terms “traditionalists” and “mutualists” to try to capture a distinction that is not so exclusive.

There is no sharp division between traditionalists and mutualists. What distinguishes them is the value they prioritize. Traditionalists give priority to exploitation, and hence are resourcists; mutualists give priority to protection, and hence are protectionists. While these labels are imperfect, they are perhaps adequate to capture various admixtures of differences in people’s sentiments, values and attitudes regarding wildlife.

Wildlife management agencies are decidedly traditionalist. They focus on protecting some species (boreal toads, for example), that people aren’t interested in exploiting and that are at risk. Other species are managed as resources for hunting (including trapping and fishing). These latter include ungulates, such as deer and elk, and large carnivores such as cougars and wolves. However, while both are valued primarily as a resource, they are not valued equally. Ungulates are valued more highly than carnivores.

#4: “Wildlife may be killed only for a legitimate purpose.” This statement is explicitly prescriptive. It means that wildlife ought not be killed for an illegitimate purpose. But what counts as a legitimate or an illegitimate purpose?

In practice, what counts as a legitimate purpose is a matter of tradition: trapping beavers and bobcats for fur is considered a legitimate purpose in most states, as is hunting deer and elk for meat (with a trophy as a byproduct). Killing cougars for trophies, and only for trophies, is deemed legitimate in most states where there are cougars. Even killing for the sheer fun of it is in some cases considered legitimate. For example, coyotes are considered vermin in most states and have no legal protection. People can kill them by just about any means, for any reason or no reason, then dump the carcasses. There are even contests in which people compete for prizes to see who can kill the most coyotes (see Project Coyote’s film Killing Games). These examples show that under state wildlife management different species of animal are relegated different status depending on which values prevail.

On a resourcist view of wildlife, the value of wild animals is something bestowed on them by humans, who may value them however they wish, so consistency across species isn’t an issue. Ungulates such as deer and elk are valued more highly than the animals that prey upon them, so management attempts to maximize the number of ungulates in part by reducing the number of carnivores.

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Coyote © KIT West Designs

How wild animals are procured, or “harvested,” as agency personnel like to say, should be mentioned in this connection too. For example, is killing a black bear over bait a legitimate way to “take” a black bear? What about all the techno-gadgetry employed in hunting nowadays, such as range finders and GPS collars on dogs—is it legitimate? More to the point: ought it be deemed legitimate?

Notice that there is no logical consistency among these examples of “legitimacy,” no general principle or rule of reason that circumscribes and justifies them all. Anything might count as a legitimate hunting purpose or method or technology, depending only on what the state-approved authorities decide. Ethics need not enter into it and rarely does.

Wildlife managers will probably disagree. For example, in some states where bear baiting is permitted, the taking of lactating sows is prohibited in order to avoid orphaning cubs, the idea being that this makes killing bears over bait more moral. (It is worth noting that it also serves to sustain a population “surplus” for future exploitation.) While this is true as far as it goes, it also misses the more basic point that rarely is the ethicalness of bear baiting seriously questioned in the first place. Never mind that baiting would clearly seem to violate the hunter “ethic” of fair chase and that it results in the killing of a sentient being—something that cries out for moral justification. On the resourcist view of wildlife, ethical considerations governing exploitation of wildlife, such as they are, are grounded in arbitrary preferences, not in ethics.

Moreover, no justificatory reason for bear baiting (for just one example) is ever adduced that is consistently applied to management of other species. For example, if killing bears over bait is deemed ethical, and therefore a legitimate killing of wildlife, what is it about bear baiting that makes it ethical whereas baiting deer and elk with salt blocks is not? In the contrapositive, what is it about deer and elk baiting that makes it illegitimate whereas bear baiting is legitimate? Whatever the considerations may be, I dare say they are not of the ethical kind. Again, none of this really matters from the resourcist perspective.

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Brown Bear © MasterImages

Other considerations aside, does the hunter’s skill and commitment of time and resources justify the killing and the method used? It is distressing how many people think so. Obviously, skill and commitment of time and resources are rationales for hunting that ignore the interests of the animals as entirely irrelevant to the question of justification. These rationales suggest that animals have no interests of their own—no legitimate ones anyway—and are properly considered a mere resource for satisfying human wants, however frivolous. This is completely at variance with what a growing body of science informs us about animal minds, as well as with how people think of their pets. The 17th century philosopher René Descartes thought that non-human animals have no souls, and hence are not sentient and cannot experience pain, let alone have interests. It takes hyper-abstract cogitations to arrive at a conclusion so far removed from common experience. You can be sure Descartes never had a pet dog or cat. Unfortunately, Descartes’ unrealistic view lives on in the resourcist view of wildlife.

Some hunters insist that they love the animals they pursue and kill. (Wolves are the most prominent exception, hated by many as the incarnation of evil.) Does the hunter’s alleged “love” for a cougar or bear he or she intends to kill justify the killing? No. Such claims are probably sincere, but they mask a deep confusion. More likely, the sentiment is admiration that is mistaken for love. In any case, it is patently obvious, upon reflection, that the alleged love of the quarry pursued by the trophy hunter is really self-love that is both inflated and masked through self-identification of the hunter with the defeated quarry. If the defeated quarry is loved, the love is secondary to and dependent upon the ego-gratification obtained by conquering and destroying it. And the greater the challenge (or the perceived challenge), the greater the conqueror is presumed to be. It is like cage fighting, where the object is to beat the daylights out of an opponent. The more difficult the challenge, the greater the glory and status of the victor among peers and fans. But cage fighters at least have a say in the matter. They don’t have to fight if they don’t want to. Furthermore, the rules give opponents a “fighting chance” and the outcome is generally not lethal. True love of a wild animal would be best shown by leaving it alone, not by killing it; and certainly not by shooting it point blank in a tree.

#6: “Science is the proper tool for discharging wildlife policy.” Notice first that, like #1, #6 is superficially a descriptive statement, but that the clear intent is prescriptive, as shown by the word ‘proper’. In other words, science ought to be used to discharge wildlife policy.

However, you can’t discharge a policy that hasn’t been formulated any more than you can fire a gun that isn’t loaded. This implies that while science might be the proper tool for discharging wildlife policy, something else or something more is required for forming wildlife policy. What is this something?

Answer: particular values and the sentiments underlying them. Facts alone do not dictate any course of action. Indeed, the only bridge from factual description to ethical prescription and consequent action is sentiment. If a person feels strongly that trophy hunting grizzlies is wrong, he or she will not engage in trophy hunting of grizzlies even given the means and the opportunity to do so. One can say of such a person that he or she values live grizzlies over hunting them for trophies. The predominate value guiding contemporary wildlife management of ungulates and carnivores alike, on the other hand, is the utilitarian value of resourcism: Manage wildlife so as to ensure a maximum sustained yield of preferred species while taking care not to drive other species to extinction. This is what the NAM is all about. It isn’t hard to see that its primary purpose is to serve the hunting culture, which happens to consist mainly of older, white men. Conservation from this perspective is for the sake of hunting opportunity. (Of secondary importance, state wildlife management is intended to serve the interests of farmers and ranchers.)

Also, shouldn’t science be used in the formation of wildlife management in the first place, especially if the management is meant to promote conservation to counterbalance resource extraction? Or is policy strictly a political matter, with science to be used solely as a tool for determining how to discharge policy most effectively so that it accords with wildlife valued chiefly as a human resource? This aside, #6 neglects the fact that in order to best promote wildlife conservation, application of science to wildlife management is more relevant at the policy formulation stage than at the policy discharging stage. #6 needs correction to acknowledge this fact.

The sciences that are most important in this regard are evolution, ecology and conservation biology because they inform us about how biological systems actually work, which ought to be considered the guide to how they work best. And this in turn should have a major influence on our sentiments and values. Instead of managing wildlife like farm animals, managers should manage ecosystems so as to restore and preserve wild processes.

State wildlife management has not caught up to this truth yet. It is not surprising, then, that state wildlife governance—the system of laws that governs management—largely ignores the interests of people who value wild animals in ways that are at variance with the bias, as well as the interests of wild animals themselves. Wildlife boards and commissions, like the authors of the NAM, are almost invariably white males steeped in the resourcist culture. Because of various accidents of history, they came to be in control. Understandably, they are determined to retain control even as society increasingly values wildlife for its own sake. The historical trend, however, is ineluctably toward greater appreciation of the intrinsic value of wild animals. Protectionism is gradually replacing resourcism.

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

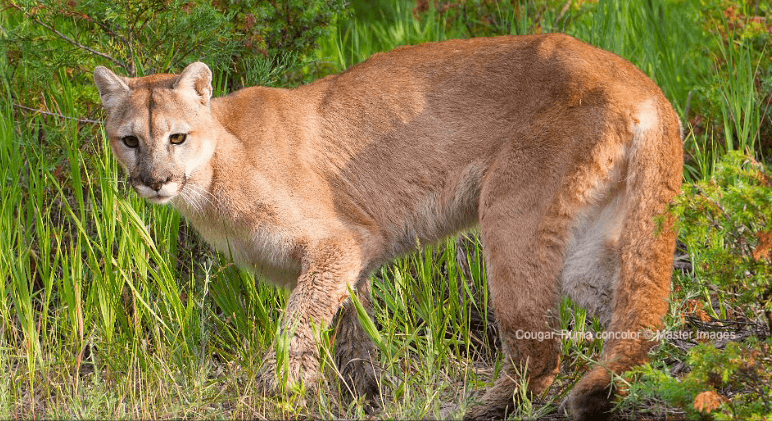

Cougar, Puma concolor © MasterImages

Now for a proposal. Because we value a pluralistic society with some semblance of democracy and equal representation, it surely behooves us all to seek ways of accommodating each other even when we disagree. What implications does this have for formulating and discharging wildlife management and conservation policy? Here’s a suggestion that I think has considerable merit: Trophy hunting, understood as hunting where typically the procurement of a trophy or any kind of personal satisfaction is the chief purpose, must be regarded as illegitimate.

This would eliminate general hunts for large carnivores and retain hunting of species where the primary goal is food procurement. It would also permit some important secondary purposes of hunting, such as achieving intimate contact with nature and obtaining a memento of the experience. Further, it would provide wildlife management and governance a more ethical unifying rational basis for wildlife management policy. Not to be overlooked, it would also accord better with NAM principle #1 by better discharging the trust to preserve ecological processes. It would have the benefit of making the concept of “legitimate purpose” at the core of tenet #4 more principled and coherent. Most important, this change would have the benefit of helping maintain, or in some cases restoring, healthy functioning of ecosystems, thus better serving an appropriately reformulated tenet #6.

In this connection, the science of ecology teaches us to think of the land broadly as a kind of organism. Carnivores and other “strongly interactive” species are critical to the healthy functioning of the land organism. Among other things, they act as a kind of immune system to check the spread of diseases such as chronic wasting disease (CWD) and brucellosis. While it is perhaps not yet proven that large carnivores in ecologically effective populations will prevent or slow the spread of these diseases, there is ample reason to think they will. Their evolutionary endowment of keen senses and powers of observation enables carnivores to detect those prey animals that are easiest and safest to kill. This promotes the survival of carnivore species and also promotes the fitness of prey species. Which is exactly what we should expect given what we know about the processes of organic evolution. Since all of us presumably want healthy functioning ecosystems, this is one value we might all be able to agree on, eventually, as people’s sentiments adjust to the dictates of reason. (It is worth noting in this connection, that CWD, which is rapidly sweeping westward through Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and Utah, is virtually absent where wolves are abundant.)

Not hunting or trapping carnivores will have the benefit of keeping populations of other animals within a narrower band, thus preventing wild swings in population sizes and consequent habitat destruction. All worries about carnivores becoming too numerous and getting “out of control” if not subjected to hunting ought to be allayed. A growing body of scientific research instructs us that populations of large carnivores such as cougars, wolves and bears are self-limiting. If left alone, their numbers will automatically adjust to what the food base can support.

Another growing body of scientific literature indicates that hunting carnivores is more likely to cause conflicts with humans, e.g., livestock depredation, than prevent them. Not least, hunting large carnivores prevents the normal cultural transmission of knowledge to future generations—knowledge of where to go, and when, to find natural food sources, and of successful hunting and foraging strategies.

Meanwhile, it must be acknowledged that a necessary step toward a resolution of competing values of wildlife must be the reformation of state wildlife governance. This will require wildlife boards and commission members who are educated in the relevant sciences and who are independent of special interests. Equally important, if not more so, it will require that wildlife boards and commissions more accurately represent the diversity of values and opinions of all citizens, not just those relative few who have a strongly vested personal interest in maintaining the status quo. How this will come about is a further question.

RE: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - Pckts - 01-29-2020

My Personal View:

Trophy Hunting...

Never acceptable

Poaching...

Never acceptable

Recreational Hunting...

Not for me but I have enough friends who do it and they have a greater respect for nature and animals than 99.9% of the other people out there I talk to.

They hike for days through the elements, they harvest the animal and eat it for months. Most of my friends still feel remorse when they make a kill and never want to see an animal suffer.

So if you're going to eat burgers, chicken, fish, steak, etc.

You really have no right to complain about someone who chooses to hunt for their food and know where it actually came from as opposed to eating something that is treated so cruelly that most people cannot even watch how they are living or killed since it hurts their hearts.

That being said, if all people chose to hunt there would be no food left, so regulations must always be in place and enforced strictly and keystone species must be protected, the removal of predators to increase herbivore numbers for hunting revenue is never acceptable either.

Most Hunters or Conservationists have the same goal and that is to protect the natural world. If we are to take on such a large task then we all need as many allies as possible. It's better to learn from one another and join forces in our fight against the ones attacking the natural world.

RE: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - LazarLazar - 01-30-2020

Trophy hunting is awesome..... IN THE VIRTUAL WORLD

To be serious

Hunting and poaching must be 10000000000000000000000000000000000000000% ILLEGAL

Hunters and poachers must be EXECUTED BY CHOPPING THEIR HEADS OFF

RE: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - Sully - 01-31-2020

@Pckts how do you respond to those who point out the conservation benefits of trophy hunting? It is something that definitely leaves a sour taste in my mouth and needs more regulation (no idiotic killings of subadults) but generally it seems to do more good than bad even if morally bankrupt.

RE: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - Spalea - 01-31-2020

I speak for wild animals...

Trophy hunting and poaching should be NEVER accepted and tolerated.

One good single reason: as concerns the struggle for life in wild, only the weakest animals (wounded, sick and so on) are eliminated, the safest individuals survive and thrive.

The human predation always kills the strongest and the most gorgeous animals: elephants with the biggest tusks, lions with the most wonderful manes, rhinos with the longest horns, tigers and bears with the most thickest furs and so on. Thus the pride or the remaining animals cannot longer survive when they are deprived of their most victorious individuals which ensured the stability of the pride or the solitary specy's survival. How many familial or clan structures have been so devastated ?

I really don't conceive how we can be able to ask this question...

RE: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - Pckts - 02-02-2020

(01-31-2020, 03:19 AM)Sully Wrote: @Pckts how do you respond to those who point out the conservation benefits of trophy hunting? It is something that definitely leaves a sour taste in my mouth and needs more regulation (no idiotic killings of subadults) but generally it seems to do more good than bad even if morally bankrupt.

The economic Benefits of trophy hunting compared to Eco Tourism in general are slim, Trophy hunting makes up the smallest % of the GDP *less than .03%* and less than 3% of that actually benefits local communities, comparing that to eco tourism which makes up 4%-6% of the GDP.

The moral issues are another set back, what kind of people want to hunt animals to simply display them in their living rooms?

I see no real benefit to trophy hunting at all, but if you ask me to choose between a Hunting park or commercial and residential buildings, of course I'll chose the Park. But I don't see that being the only 2 options very often so it's a moot point.

RE: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - Sully - 02-06-2020

Dead elephant walking: Why hunters in Calgary shouldn’t be granted a licence to kill

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/5JEUK6XGYFAB5CM6AYOWBI3F4M.JPG)

*This image is copyright of its original author

An elephant roams the Duba Plains in northern Botswana on Nov. 29, 2016.

JOAO SILVA/THE NEW YORK TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Judy Malone writes for Tourists Against Trophy Hunting, an international coalition of scientists, naturalists, journalists and wildlife advocates.

Somewhere in Botswana is a dead elephant walking. He is an individual in his prime. Very few mature bulls today live to old age with tusks that sweep the ground, and nor will he. In January, he was sold to a trophy hunter at the Calgary International Hunting Exposition, hosted by the Calgary chapter of Safari Club International (SCI). After days of public backlash, the club withdrew the elephant hunt from an evening auction, with a starting bid of $84,000, telling members it would be a direct sale. The hunt will take place in the spring, among the first in Botswana since the lifting of a five-year ban.

Botswana took a progressive stand in 2014 when its government announced trophy hunters were no longer welcome. Evidence of the abuse of hunting privileges was rampant, and communities were not benefiting from the fees that hunters were paying. The ban was applauded by conservationists and gave hope that sport killing of already critically-threatened wildlife would end. But a country that was leading the way in conservation and ecotourism is again back to killing wildlife for pleasure and profit.

Elephants are highly intelligent, with complex social behaviours that parallel those of humans. They are very aware that ancestral migration routes have become minefields blocked either by fences or by people with guns. Understandably, they have tended to linger in a country that was bent on protecting them. But there have long been warnings that poaching would follow them to Botswana, and it has. The ivory trade has reached what was a last safe haven. With the trophy hunters also back in force, elephants are in trouble.

The lifting of the hunt ban was not about overpopulation of elephants; it was about elephants becoming a political football. While Botswana is home to just over a third of Africa’s remaining herds, the population has remained stable for years. A new interim government looking to be elected used incidents of crop raiding to whip up anti-elephant pro-hunt sentiments and collect rural votes. The hunting of a few hundred select trophy males in any case hardly contributes to population control. But corruption in African governments runs high, and SCI influence runs deep in countries where it wants access to game. SCI reported to members it was meeting frequently with Botswana’s President Mokgweetsi Masisi to extend “support” for his hunting-reintroduction efforts.

On a Facebook post promoting the hunt, SCI-Calgary told its members Botswana elephants are “tremendously overpopulated” and “native villagers are in harm’s way from marauding elephants.” None of it had the ring of science or reality.

The official SCI conservation claim goes like this: Well-regulated trophy hunting generates revenue for communities, provides an anti-poaching presence, creates employment opportunities and increases tolerance of wildlife presence. It may be that middle-aged men draped over dead animals doesn’t look much like conservation, but conservation it is, or so the narrative goes. The science SCI offers up as evidence that killing individuals saves populations is funded by or has a dotted-line connection to the hunting industry or governments that profit from the industry.

What the industry says to justify what it does is unsupportable, and there are many published reports proving it. Some come through the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Although IUCN controversially admitted trophy hunters as members in 2016, its scientists have written since that hunting is inconsistent with sustainability objectives, threatening moral and ethical leadership in conservation.

What trophy hunting does very well is contribute significantly to wildlife declines by removing from populations the biggest and best individuals with the most life experience. The “old bulls” are in fact in their prime, and shooting them kills future generations. One reason big-game hunting in Africa is itself in decline is the loss over many decades of trophy-calibre animals left to kill.

The difference between poaching and trophy hunting is a legal permit. In both cases, tusks are removed from dead elephants. Last week, one more permit was sold, and one more elephant soon extinguished.

In February, Botswana’s President will fly to Reno, Nev., to collect his own trophy as SCI “international legislator of the year.” SCI is rewarding Mr. Masisi for taking bold action to welcome its members back “even if it meant facing fierce criticism from uninformed anti-hunting activists in both his own country and in Western countries.”

In a time of staggering loss of wild-animal populations and global biodiversity, how can we possibly continue to allow what conservationist Rachel Carson called this “moronic delight” in killing, which sets back the progress of humanity?

The move to ban trophy-hunting imports by Western governments is growing; a ban by the United Kingdom is now in a public-consultation period. Canada is the world’s leading exporter of hunting trophies to the U.S., ahead of any African country. Our wildlife populations are in free fall, and one of the multiple threats they face is hunting. Isn’t it time for our federal government to step up with a ban on trophy imports and exports?

RE: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - TigerJaguar - 02-08-2020

Just a thing are you guys for or against zoos

RE: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - Sully - 02-10-2020

(02-08-2020, 11:53 PM)TigerJaguar Wrote: Just a thing are you guys for or against zoos

There is a thread specifically about that

RE: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - TheNormalGuy - 02-28-2020

I and my father hunt for food and pleasure.

We hunt White-Tailed Deer and Moose.

Moose Legislation in our area in QC, Canada change every year, in a 3-way format.

One year, it is Bull, Cow and Calf Moose. Then, the next year, it is only Bull and Cow And then only bull moose.

That way the calves can grow in the second year and mate with the cows in the third year.

We are allowed one moose by 4 permits and it costs around 25-50 $ CA (20-40 US) for one permit.

We usually let the trophy bulls go since they are the best genitors as we do in fishing. [Walleye ranging under 37 cm are released as are those above 57 cm] [The More the fish is big, the more it lays eggs]

However, the United States and Some African countries aren't ethic in many ways. Lower states like Texas, Arizona, Nevada and South Africa make hunting locations for exotic wildlife.

I don't really like the concept. Even more, that these are fenced locations. You already know that the animals are there..... Just need to find them.

Blackbuck and Barbary Sheep are amongst the most hunted animals in these fenced ranchs in the USA.

As for South Africa, they breeds intentionnally animals for rares fur variations.

Crowned Wildebeest, White-Flanks Impala, etc... for exorbiting price and the demands just get bigger and bigger by the years.

RE: A discussion on the ethics and practical function of hunting - TheNormalGuy - 02-28-2020

In South Africa, Ranchers Are Breeding Mutant Animals to Be Hunted

Rich marksmen pay a premium to shoot “Frankenstein freaks of nature”

By Kevin Crowley | March 11, 2015

It’s easy to spot Columbus. He’s not only the biggest and strongest gnu among the dozens grazing on a South African plain, he also sports a golden-hued coat, a stunning contrast to the gray and black gnus around him.

Finding Columbus in the wild would be a stroke of amazing luck. More than 99.9 percent of all wild gnus, also called wildebeest, from the Afrikaans for “wild beast,” have dark coats. But this three-year-old golden bull and his many offspring are not an accident. They have been bred specially for their unusual coloring, which is coveted by big game hunters.

These flaxen creatures are the latest craze in South Africa’s $1 billion ultra-high-end big-game hunting industry. Well-heeled marksmen pay nearly $50,000 to take a shot at a golden gnu — more than 100 times what they pay to shoot a common gnu. Breeders are also engineering white lions with pale blue eyes, black impalas, white kudus, and coffee-colored springboks, all of which are exceedingly rare in the wild.

“We breed them because they’re different,” says Barry York, who owns a 2,500-acre ranch about 135 miles east of Johannesburg. There, he expertly mates big game for optimal — read: unusual — results. “There’ll always be a premium paid for highly-adapted, unique, rare animals.”

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Left: A standard lion. Photographer: Getty Images

Right: Letsatsi, the white lion. Photographer: Arno Meintjes/Getty Images

This kind of selective breeding to create exotic animals has raised howls from conservationists and more traditional hunters, who dismiss the practice as little more than creating mutants for profit. “These animals are Frankenstein freaks of nature,” says Peter Flack, a hunter and conservationist and former chairman of gold mining company Randgold Resources. “This has nothing to do with conservation and everything to do with profit.”

No one disputes that there’s money to be made in rare big game. Africa Hunt Lodge, a U.S.-based tour operator, advertises “hunt packages” to international clients traveling to South Africa that include killing a golden gnu for $49,500, a black impala for $45,000, and a white lion for $30,000. For the money, hunting tourists typically get a seven- to 14-night stay in a luxury lodge, gourmet food with an emphasis on meat dishes, and hunting permits. (Taxidermy costs extra.)

Operators don’t guarantee kills, yet to leave hunters disappointed is generally seen as bad business, says Peet van der Merwe, a professor of tourism and leisure studies at South Africa’s North-West University. Killing lions was the biggest revenue generator for the country’s hunting industry in 2013, followed by buffalo, kudu, and white rhinos.

As the hunting industry has grown, so have the numbers of large game animals that populate South Africa’s grasslands. In other parts of Africa, including Kenya and Tanzania, the opposite has been true: Large mammal populations have been decimated as farms and other human activities encroached on wild areas. But South Africa is one of only two countries on the continent to allow ownership of wild animals, giving farmers such as York an incentive to switch from raising cattle to breeding big game. ‘‘My first priority is to generate an income from the animals on my land, but conservation is a by-product of what I do,” York says.

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Left: A standard golden impala Photographer: Villy Yovcheva/Getty Images

Right: A White Flanked Impala at Phala Phala Wildlife in Bela Bela Source: Phala Phala Wildlife

At 66, York has been involved in breeding and hunting for decades. After he emigrated from his native Zimbabwe in 1980, he bred prize cattle for beef in South Africa’s northern grasslands. He also organized hunts, which gave him the occasion to see his first golden gnu in 1986, when a client killed one. “It was the most beautiful animal I had ever seen,” he says.

[And then you you want to bred some just for them to be raise up to be killed, oh no a swear word you] - The Normal Guy

In 2007, York bought a farm in Limpopo Province that had previously been used for crops. His plan was to raise beef cattle. That turned out to be a costly mistake. The cows languished, unable to gain weight and poorly adapted to the ticks and other pests prevalent on the hot plains. York found himself shelling out a steady stream of cash for expensive vaccines and veterinary fees. At that rate, “I’d be broke in a year or two,” he says.

York recalled the beautiful golden gnu he had seen more than 20 years earlier and hatched a plan. He figured that, as a native species, gnus were better adapted to the South African grassland than cattle. He would be able to sell them for both hunting and meat, and if he could breed some with exotic coloring, they would command a premium.

His timing was good. The switch coincided with a rise in popularity of big game hunting, and prices for rare variants were soaring.

Since 2005, the average price at auction for a golden gnu has more than quadrupled to 404,000 South African rand ($33,000).

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Barry York Photographer: Dean Hutton/Bloomberg

Letter to the Editor: Wildlife Ranching and Breeding in South Africa, by Richard York

Today, York has roughly 600 gnus. He keeps the best — the most fertile and beautiful, with the biggest horns — for breeding. The next tier goes to auction, mostly for sale to other breeders. Animals that don’t make the grade for breeding are sold to hunting ranches, which are typically bigger and more scenic than York’s, giving hunters the feel of the wild African bush. York allows the least-desirable animals to be shot by local hunters for food.

A drive around York’s spread reveals little evidence of its former life as an intensive crop farm growing potatoes, corn and peanuts. Long native grass flickers in the wind as the gnus graze peacefully. The only signs of man are the electric fences York uses to separate his herds. Since he took over the farm, jackals, bat-eared foxes, and caracals, as well as troops of monkeys, have appeared on the land.

“Previously this was crop land with pesticides, chemicals, very few trees, no wildlife,” he says. “Now there are hundreds of wildebeest where there were none for 100 years. The color variants are paying for it.”

Breeding exotic big game is also attracting South Africa’s wealthy, including billionaire Johann Rupert, who controls the world’s largest jewelry maker Cie Financiere Richemont, as well as Norman Adami, ex-chairman of the South African unit of SABMiller, and Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa. Two years ago, Rupert led a group that paid 40 million rand, for a buffalo named Mystery, specifically bred for his large horns. Ramaphosa, one of South Africa’s wealthiest men, sold impala with white flanks (they are normally copper colored) for 27.3 million rand last September. The same year, York sold a male golden gnu named General Rommel for 1.83 million rand.

“Everyone wants wildebeest,” says York, who received 10 calls from people wanting to buy while a Bloomberg reporter was recently visiting his farm. “We haven’t got enough stock. It’s every day, new people wanting to get in.”

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Left: Wildebeest walking the plains of Etosha National Park. Photographer: Getty Images.

Right: A golden wildebeest, also known as a gnu, grazes on farmland operated by Golden Breeders in Bela Bela. Photographer: Dean Hutton/Bloomberg

The country now has about 22 million large mammals, including lions, buffalo and many species of antelope, three-fourths of which live on private ranches. Hunting ranches have been widely credited with saving the rhinoceros from extinction in the 1960s, when there were just an estimated 575,000 large wild animals in the country.

“Not a single country in the world has seen such a large increase in animal numbers over the last 50 years,” said Wouter van Hoven, an emeritus professor at the University of Pretoria. “It’s an incredible success story.”

Despite the increase in populations of native species, conservationists deride the methods used by York and his fellow breeders. “What’s happening now is farming,” says Ainsley Hay, manager of the Wildlife Protection Unit of South Africa’s National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. “It’s not conservation. It doesn’t matter if you’re farming cows or impala, it’s a damaging form of land use.”

And in this case, growing numbers of animals don’t indicate conservation, she says. “A white springbok will not contribute to the springbok population because it’s a mutant.”

The NSPCA, which has sent inspectors to game farms and wildlife auctions, Hay says, most color variants would not survive in the wild. White lions get skin diseases, cancers, foot problems, and corkscrew tails. Their faces turn inward, and “white springbok variants are very prone to skin cancer,” she says. “It’s been scientifically proven that black impala are more susceptible to heat stroke.”

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Left: A standard kudu Photographer: Chris Hill/Getty Images

Right: A kudu doe grazes on farmland operated by Golden Breeders in Bela Bela, Limpopo region of South Africa. Photographer: Dean Hutton/Bloomberg

Local hunters have a different critique. Flack, the former Randgold chairman, and others claim that breeders are domesticating wildlife, which could threaten the long-term viability of the hunting industry. The South African Hunters and Game Association, a local industry group, last month published a stinging indictment of breeding, saying it amounts to “unnatural manipulation of wildlife” and causes “outrageous prices of huntable animals.”

York dismisses the hunters’ objections, saying they simply want to be able to hunt cheaply. To the NSPCA, he says that he avoids inbreeding by keeping herds separate and that his land is much healthier than when he bought it. As to Flack's charges, York says: “They say these are Frankenstein animals, but where’s the test tube, where's the lab? Sure, the golden color is a rare characteristic, but it occurs in nature.”

York is looking forward to July, when Columbus will be sold at auction. The bull is ready to mate. He sports a horn spread of 30 inches, the length of a softball bat. Does he have a chance of breaking the record 3.4 million-rand paid for a golden gnu? York won’t speculate: “We don’t want people to think we’re arrogant.”