+- WildFact (https://wildfact.com/forum)

+-- Forum: Information Section (https://wildfact.com/forum/forum-information-section)

+--- Forum: Terrestrial Wild Animals (https://wildfact.com/forum/forum-terrestrial-wild-animals)

+---- Forum: Wild Cats (https://wildfact.com/forum/forum-wild-cats)

+----- Forum: Jaguar (https://wildfact.com/forum/forum-jaguar)

+----- Thread: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars (/topic-modern-weights-and-measurements-of-jaguars)

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Dark Jaguar - 03-19-2020

credits: Onças do Rio Negro

https://www.facebook.com/oncasdorionegro/photos/a.1036369863051784/1117704208251682/?type=3

credits: Instituto Onça Pintada ( IOP )

http://jaguar.org.br/primeira-onca-pintada-femea-capturada-fotos/

Barbie pregnant pantanal female 85 kilos ( she was pregnant of just one cub )

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

She gave birth a few weeks after the capture.

After a few months Barbie and her one single cub ( a female ).

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Pckts - 03-20-2020

(03-20-2020, 09:46 PM)Dark Jaguar Wrote: credits: G1.globo.com

Juru male 120 kilos.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Official link (portuguese) - https://g1.globo.com/natureza/desafio-natureza/noticia/2019/07/02/turismo-tecnologia-e-ciencia-cidada-ja-identificaram-pelo-menos-400-oncas-pintadas-no-pantanal.ghtml]https://g1.globo.com/natureza/desafio-natureza/noticia/2019/07/02/turismo-tecnologia-e-ciencia-cidada-ja-identificaram-pelo-menos-400-oncas-pintadas-no-pantanal.ghtml[/url]

Last year 2019 the G1 reporters from Globo ( the biggest Brazilian/latin america tv channel ) were fortunately enough to have made a trip of 10 days to northern pantanal to discuss about illegal fishing, illegal hunting and jags conservation with many projects interviewing members such as Panthera researcher Rafael Hoogesteijn, Fernando Tortato, Nilto Tatto, Jaguar Ecological Reserve members, Instituto Homem Pantaneiro, Alexandre Bossi president of ONG SOS Pantanal.

During their boat tour along with the researchers, G1 team reporters were lucky enough to find Juru male Jag ( check their trip/visit in the video of the official link above including Juru encounter at 4:16m ) and posted about him (and his weight) and jags population increase in northern pantanal on their page.

@portalg1

''This is the jaguar Juru, a five-year-old male weighing 120 kilos who dominates a region of Porto Jofre in the Pantanal region. Thanks to a change in the behaviour of the Pantanal local people, The population of the species has grown. You wanna know what they've done? go to G1 stories'' https://gramho.com/media/2080077428692490681

Their encounter/sighting of Juru during boat tour. photos: @edupalavideo/G1

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Same account on other pages ( in portuguese )

Instituto Homem Pantaneiro: https://www.facebook.com/ihppantanal/posts/2389683811090352/

Others:

https://www.poconet.com.br/noticias/ler/turismo-tecnologia-e-ciencia-cidada-ja-identificaram-pelo-menos-400-oncas-pintadas-no-pantanal/13325

https://gramho.com/media/2080077428692490681

( In comparison he is a little bit smaller than Sombra male 122 kilos from southern Pantanal )

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

I can't believe Juru is 120kg!

He's one of the smallest male in the North, I can't imagine what Balwin weighs!

Balwin was said to be one of the males that Dwarfed Adriano.\

My photos of him

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Paulo's shots of him

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

compared to my shots of Juru/Marley

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

Here's a great post where you can see the modest size of Juru with Ague compared to Aju with Ague

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Pckts - 03-21-2020

(03-21-2020, 08:59 AM)Dark Jaguar Wrote: Yeah Juru size was quite surprising for me too. this was the info they stated under the trip video in the website and to be honest with you just the fact of them meeting up with all those important people who works with jags to interview/research as you saw on the video/pages is what really made me post this otherwise I wouldn't.

about Balwin I already knew he is a big one. he should definitely be measured. to dwarf Adriano takes him to a whole other level and we both know he is up there. Do you have more photos of him up close?

I dont unfortunately but I did get to see him and the Hunter female for quite some time.

To me, the hunter female was almost as large as Marley when Blawin was with her he was much larger. You can see Balwin compared to Marley in the fight video where they come rolling down the hill and Marley then runs off with Balwin in hot pursuit.

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Dark Jaguar - 03-22-2020

Projeto Onças do Rio Negro

https://www.facebook.com/oncasdorionegro/posts/1035112733177497

Pantanal Jag vs Caatinga Jag

Projeto onças do rio negro - ''How can it be? Two male jaguars, one from the Pantanal biome and the other

from the Caatinga biome (Northeast Brazil). both with approximately 5 years of age but one weighing 130 kg and the other 37 kg.''

Southern Pantanal male 130 kg

*This image is copyright of its original author

Caatinga male 37 kg

*This image is copyright of its original author

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Dark Jaguar - 03-26-2020

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Dark Jaguar - 03-27-2020

2 Atlantic Forest males.

71 kilos Atlantic Forest male jag

https://www.vidasilvestre.org.ar/nuestro_trabajo/que_hacemos/nuestra_solucion/cambiar_forma_vivimos/conducta_responsable/bosques/yaguarete/?4044/Tras-los-rastros-del-yaguaret#

Guacurarí, the first jaguar monitored by a GPS collar in the framework of this project was captured in 2009 in the Iguazú National Park. It is a 71 kg adult male who had already been photographed in camera-trap sampling carried out by the same researchers (Agustín Paviolo, Mario Di Bitetti and Carlos De Angelo) in 2006 and 2008.

*This image is copyright of its original author

70 kilos Atlantic Forest male jag

https://tribunaonline.com.br/onca-pintada-e-capturada-com-o-uso-de-tecnologia

The capture of the animal a 70 kg male was carried out by researchers from the Felinos Project and it is one of the few of this species already carried out in the Atlantic Forest throughout the Brazilian territory.

*This image is copyright of its original author

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Dark Jaguar - 03-27-2020

Credits: Londolozi

2 Pantanal Jaguars from Refúgio Ecológico Caiman ( Caiman Ecological Refuge ) Southern Pantanal.

https://blog.londolozi.com/2011/12/01/the-whereabouts-of-jaguars/#gallery

https://blog.londolozi.com/2011/11/05/jaguars-macaws-and-the-pantanal/

85 kilos female

she's about 5 years old.

*This image is copyright of its original author

''It was an unique experience to work with the Americas’ largest wildcat surrounded by the sounds of the Pantanal rain. It was a beautiful female weighting 85 kg and about 5 years old. The whole process of setting the GPS collar was done quickly and in less than two hours she was recovering herself already.''

*This image is copyright of its original author

''Her coat was wonderful without any apparent marks, a healthy young adult.''

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

*This image is copyright of its original author

110 kilos male

''It was a spectacular morning. Being close to this undengered animal is a unique opportunity for those working in conservation and ecotourism. This was a big jaguar male, with powerful muscles, huge paws and prominently large jaw and at the same time showing a smooth behavior.''

*This image is copyright of its original author

''This beautiful cat weighed 110 kg, having all the necessary tools to defend its territory and compete for females. With an estimated age of 7 years old, this jaguar was very healthy with well-preserved teeth and in reproductive period.''

*This image is copyright of its original author

''Check out the look of this great jaguar, although still without a specific name. Perhaps with this history someone can come up with an interesting name for him.''

*This image is copyright of its original author

Check out Londolozi special article in the links bellow about Caiman Ecological Refuge during the trip of the 2 Londolozi professional african trackers Andrea and Richard to the Pantanal-Brazil. There they joined Onçafari team.

In both articles and interview the Londolozi's african trackers state Fantasma male (bellow) is the same size as a Lioness.

*This image is copyright of its original author

https://blog.londolozi.com/2013/06/09/projeto-oncafari-gets-a-blog/

https://blog.londolozi.com/2013/10/05/an-interview-with-the-jaguar-trackers/

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Pckts - 03-28-2020

*This image is copyright of its original author

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Pckts - 03-31-2020

From Fernando Rodrigo Tortato

He's the one who took over the field work from Rafael Hoogesteijin that I've mentioned in the past.

Recapture of the arrow! Female painted jaguar with 93 kg

*This image is copyright of its original author

Male M10, Trapezio, captured and re-collared last evening - a 106 kg male. Shown here with whole capture crew, from left Joares May, Peter Crawshaw, Allison Devlin, Jacqui Frair, and Fernando Tortato

*This image is copyright of its original author

New jaguar caught this morning, Zumbi, a 75 kg male. He is sedated here, and has recovered nicely wearing his new GPS collar. Shown here with, from left, Fernando Tortato, Joares May, Allison Devlin, and Jacqui Frair.

Young Male

*This image is copyright of its original author

Hello. My name is Butterfly, I'm a quiet cat, adult +- 90 kg, strong

*This image is copyright of its original author

Fernando Rodrigo Tortato He was captured in July Alessandro. Weighed 115kgs and is very strong. The female must be at most 70 kg.

*This image is copyright of its original author

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Pckts - 04-02-2020

119kg 4 year old!

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Pckts - 04-02-2020

(01-02-2020, 05:47 PM)Pckts Wrote: I received word on Jokers body measurementsI got Shaka's measurements too

Joker was 236 cm long (from the head to the tip of the tail), 76 cm tall, 126 cm of chest circumference, 66 cm of neck circumference

Compared to Almeidas

"The greatest height at the shoulder recorded by us was 32''; the average shoulder height of 29 male Pantanal jaguars came to 26.28''

"The height of a jaguar is a good indication of its size. Another good indication is the girth (circumference) of the body directly behind the shoulders and at the middle of the belly.

Largest girth behind the shoulder we have annotated is 43'', but Pantanal males average 40'' and females 36''

"A female who had utterly gorged herself showed the extraordinary girth of 44.5'' around her stomach, a measurement only a few males ever surpass. The record stomach girth, however, belonged to a male whose belly was empty, except for some hair. It went 47"

"The largest head circumference we have recorded is 30.25"; the average for 31 Pantanal males is 27.77", for seventeen Pantanal females 23.82. The largest neck circumference for a male is 27"; the average neck girth of 28 males is 24.93", of 16 females 21.44"

"The largest girth at shoulder of a male went 25.5'', of a female 22''. The average of 30 males 22.23'', of 17 females 18.94''. Several Males showed a forearm girth of 17'', though the average of 30 males is 24.93'', of females 13.65''

Joker vs Almeidas

6" thicker at the chest than Almeidas Largest Jag and 2" larger than the record girth he mentions.

1" Less in the neck than Almeidas Largest Jag

His body Length including his tail is very long.

29" Shoulder height *taller than average but shorter than record height*

Overall Joker is a long Jaguar with a fairly tall shoulder height and a large neck but he is immensely massive in his chest girth.

I'd love to know some of the Northern Panatanal measurements from modern times but I've had no luck as of yet.

Shaka's measurements

Shaka's body measured 237 cm in length (head: 37 cm, body: 135, tail: 65)

78cm shoulder height

Chest circumference: 108, neck: 64

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Dark Jaguar - 04-07-2020

Not sure if you guys have already seen this content. For those who have not seen it before its very interesting and informative. I've been working on translating this in a while and waiting the right moment to post.

First I'd like to say thanks to https://www.deepl.com/home for helping me with the translations and Google Translate too. I went over the details to make sure its accurate.

Not sure if this ( and my next ) post belong here or another different thread because there's actually more than weight and measurements on jaguars.

This is the dynamics and study on jaguars by George Schaller and Peter Crawshaw in the late 70's and early 80's from another point of view in that era other than the records of hunters from that time, jaguars tough lives back that time because of humans and also the average size of a female Pantanal jaguar ( 75kg ) stated by Richard Mason himself as well as the heaviest male Pantanal jag caught by him back then and the weight of considered adult sized male Pantanal jaguar back then and more.

note: Just reminding again Let's take in cosideration that all the further study content in this post took place back in the late 70's and early 80's and all the publications dates/months/year are from the source website bellow.

credits: https://www.oeco.org.br/

Introduction

Onça-Pintada: 3 decades of scientific publications

Silvio Marchini*

Published in December 21st 2010 https://www.oeco.org.br/colunas/silvio-marchini/24666-onca-pintada-3-decadas-de-publicacoes/

Atlantic Forest Jag.

.jpg)

*This image is copyright of its original author

The jaguar occupies an exceptional position in the most diverse forms of man-made recording, from cave paintings to be printed on our 50 reais ( brazilian currency ) money note. In scientific literature however it has had a relatively minor presence. Only in the last three decades have scientists described the habits of jaguars in nature. Zoologist George Schaller founded the ecological literature about the species and currently his legacy is more present in Brazil than in any other country.

In 1978, George Schaller and José Manuel Vasconcelos published the article Jaguar Predation on Capybara ("Predation of Capybara by Jaguars"). The name of the periodical in which they published the article is almost unpronounceable to most Brazilians - Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde - but the publication was the result of research conducted in Brazil, more precisely in the Pantanal of Mato Grosso do Sul ( south pantanal ). With the article, Schaller and Vasconcelos founded the modern era of ecological literature on jaguars, both in Brazil and internationally.

Not that jaguars had not attracted the attention of scholars until then. On the contrary the largest and most fascinating terrestrial predator of our country has always been highlighted in the chronicles of the explorers and naturalists who ventured into the interior of Brazil. The first report on jaguars in the country dates from 1557 and was made by the German sailor Hans Staden. In his book Two Journeys to Brazil Staden reports that "there are also many jags in that land, which spoil men and cause much damage". The work of Staden and other explorers of the 16th century defined the tonic of what would be written about jaguars in the following centuries: their predatory habits especially when perceived as a threat to man and his domestic animals and their persecution by hunters and farmers. Among the naturalists of the 18th and 19th centuries, notably Rodrigues Ferreira, Spix, Wallace and Bates, the food ecology of the jaguar was also a recurring theme although descriptions of jaguar hunts deserved significant space in their chronicles.

It was precisely reports of hunting in Brazil more specifically in the Pantanal that dominated the literature on jaguars in the first three quarters of the 20th century. The first and perhaps most influential author of this period was Theodore Roosevelt. In 1913 the hunter and former president of the United States joined Cândido Rondon on an expedition to clear the "wild Brazilian west''. During his time in the Pantanal, Roosevelt participated in jaguar hunts, which he described the following year in his book Nas Selvas do Brasil. Another legendary adventurer who left a detailed record of his hunts was Sasha Siemel. Born in Latvia Siemel spent part of his life in the Pantanal where he gained notoriety as the only white man able to hunt jaguars with a zagaia (the zagaia is a long spear that must be held tightly by the hunter so that the jaguar when thrown on him is impaled). In 1953 Siemel published his memoirs as a jaguar impaler in the book Tigreiro! Finally in 1976 Toni de Almeida published the book Jaguar Hunting in the Mato Grosso and Bolivia. Almeida was a hunter and guide of hunting safaris for foreigners but had the habit of writing down the weight size and stomach contents of the jaguars he killed. He was the first to do that. As a result, his book provided the most complete information on the biology and ecology of jaguars in the Pantanal before Schaller.

It is not surprising, therefore that Schaller chose the Pantanal to conduct the first scientific study on jaguars. Schaller came to Brazil in 1977 to study the ecology of the jaguar and its prey in a joint project between the New York Zoological Society (now the Wildlife Conservation Society - WCS) and the IBDF (now Ibama). In 1978 the Brazilian Peter Crawshaw became the national counterpart in the project. Together they were the first to use necklaces with radio transmitters to investigate the movement of jaguars. In 1980, they published the article Movement Patterns of Jaguar. In the same year Schaller moved out of the country leaving north American Howard Quigley in his place. Crawshaw and Quigley started working on a farm in Miranda and together they published several articles about the Pantanal jaguar between 1984 and 1992. Crawshaw continued his work on jaguars and today responds for more publications on ecology and conservation of the species than any other researcher.

It was only in 1986 that research on jaguars conducted in other countries began to be published. That year the North American Alan Rabinowitz published two articles on ecology and predation problems of domestic cattle in Belize in addition to the book Jaguar in which he describes his effort to create in that country the first reserve dedicated to the conservation of jaguars. Rabinowitz, who began his work in Belize in 1983 at the invitation of Schaller, laid the foundations for a long-lasting research program which today accounts for much of the ongoing research. Also in 1986, veterinarian Rafael Hoogesteijn published his first article on the situation of jaguars in Venezuela. Hoogesteijn was the author of several influential publications in the following two decades, among them the Manual on the Predation Problems Caused by Jaguars in Cutting Cattle. Together with other researchers also dedicated to the study of the ecology and conservation of jaguars on large cattle farms in the Venezuelan Lhanos, Hoogesteijn has made Venezuela one of the countries that has contributed most to the scientific literature on jaguars.

Since the mid-1990s Mexico, Argentina, Bolivia and the United States have made important contributions. Other countries that have also produced publications are Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Panama, Paraguay and Peru. In 1999, WCS and the National Autonomous University of Mexico gathered in that country 30 experts in jaguars, representing 10 countries including Brazil to present updated information on various lines of knowledge about the species. The results were published in 2002 in El Jaguar en el Nuevo Milenio, the largest compilation of articles on jaguars in a single volume ever published. Nevertheless Brazil the cradle of research on jaguars continues to be the country with the largest number of publications on the species. The expressive and growing number of professionals dedicated to research on jaguars in the country and the support of influential national and international institutions such as Pró-Carnívoros, Instituto Onça-Pintada, WCS and Panthera suggest that Brazil's leadership in research conservation and consequently scientific literature on jaguars will continue in the coming years. Thirty years later George Schaller's legacy remains more present in Brazil than in any other country.

* Silvio Marchini, Biologist Projeto Conviver Gente e Onças Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) University of Oxford.

Schaller in Brazil and the "Epitaph for a jaguar"

Peter G. Crawshaw Jr.

Published in June 9th 2014 https://www.oeco.org.br/blogs/rastro-de-onca/28399-schaller-no-brasil-e-o-epitafio-para-uma-onca-pintada/

The modern era in the study of carnivores in Brazil began with the arrival of biologist George Schaller in April 1977 to make the first study of the jaguar in the Pantanal of Mato Grosso. Here I use a text that I translated from George to tell a little more of this story. Published in 1980 this article tells the misfortunes that marked the beginning of our project with jaguars to which I formally joined in January 1978, as the Brazilian counterpart of the project through an agreement between the Brazilian Institute of Forest Development/IBDF (the precursor of IBAMA) and the Brazilian Foundation for Nature Conservation/FBCN.

After exploring areas in Central and South America, George chose for the study the Acurizal farm then an active cattle ranch located on the right bank of the Paraguay River where he is bordered by the Serra do Amolar the western edge of the Pantanal and border with Bolivia.

The original article "Epitaph for a Jaguar" was first published in Animal Kingdom Magazine, April/May 1980 and then republished as a chapter in the book "A Naturalist and Other Beasts - Tales from a life in the field", Sierra Club Books, 2007.

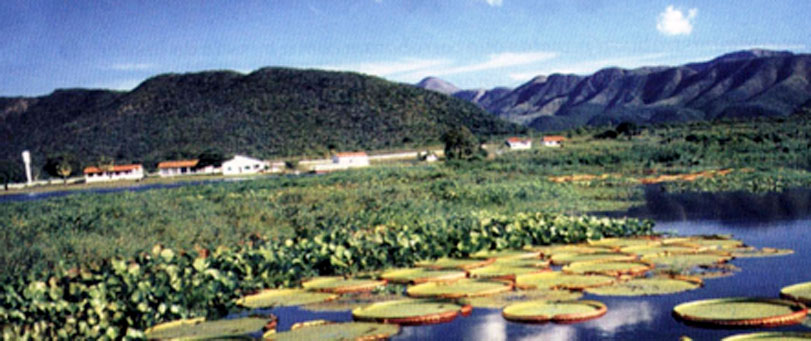

Acurizal Farm on the western edge of the Pantanal border with Bolivia. Photo: Mario Friedlander, Collection of the Ecotrópica Foundation

*This image is copyright of its original author

I pass the word to George:

"Footprints in the mud told the story. During the night a female jaguar, protected by a bush by the bay had approached a capybara and jumped killing her in an instant of violence, before she could escape to the safety of the water. Then, with the 35 kg rodent between her front paws, she lifted it up with her jaws and dragged it along the beach to the interior of the forest.

I followed the marks through sharp bromeliads like razors and thorny vines. One step at a time I went forward with my ears open. My eyes were trying to penetrate the vegetation striving to see the jaguar. It certainly knew of my presence, for the dry leaves on the ground in August made quite a noise under my feet. Perhaps she had abandoned her prey after a hasty meal, as jaguars commonly do.

Then, a few meters away a low continuous growl made me stop. Slowly I stooped down, hoping to see at least a glimpse of the luminous drawing of black rosettes on a golden background, beneath the shadowy bushes where she was hiding with her prey. But she remained invisible. Without wanting to disturb her any further, I turned back, once again frustrated in my attempts to see her. Several months ago, I was studying jaguars in Brazil at the Acurizal farm which covers 142 km² of the Paraguay River floodplain on the eastern side of the Amolar Mountain Range, a mountain range along the border with Bolivia.

During this time I had become familiar with jaguars on the farm but only in the distance through the tracks left by them along cattle tracks and beaches and examining the carcasses of their prey. It is not difficult to identify individuals by their tracks when only a few animals inhabit an area. The footprints of an adult male can be distinguished from those of a female by its larger size more rounded shape and by the greater distance between its fingers the footprints of a young animal are smaller than those of an adult and may be accompanying or close to those of a female. When two adult females occupy the same area it can be difficult to differentiate their footprints, but they usually have some characteristic that identifies them, such as some small peculiarity in the shape of the plant pad.''

Mother and cub

In Acurizal, I discovered that two jaguars an adult female and her cub, also female with an estimated age between 15 and 18 months hunted together in a forest area of approximately 40 km2. The relatively open forest provided them with cattle - their main prey on the farm - and denser stretches of secondary forest housed peccari poles, another of their most important prey. Gallery woods accompanied two streams that drained the mountain range and these sheltered other species of prey, such as deer (mateiro and catingueiro) and tapirs. The temperature was cooler ( more fresh ) inside the forest, and the jaguars often rested there during the hottest hours of the day. A third female visited Acurizal intermittently, her area partially overlapping that of the other two females. And finally a medium-sized adult male dominated not only the farm area but also extended his movements through the forests west of the mountains.

This land tenure system - with territories of neighboring females overlapping and that of a resident male including several females - is similar to that of other large lonely cats. Although they are part of a community where members monitor each other jaguars like tigers and pumas essentially live alone. Judging by their footprints, even the adult female and her daughter rarely associated. On one occasion, the male and the mother were walking together, perhaps because she was in heat/estrus. Peter Crawshaw my Brazilian colleague followed them to where they had killed a giant anteater - as a joke, apparently, because they merely bit the animal in the back of the head and abandoned it.

The morning after the female growled at me, I left the camp to explore a beach, between the water line and the forest, once again trying to find the jaguar. To my right was the Pantanal a floodplain of over 100,000 km2 which is partially flooded every year by the Paraguay river and its tributaries. This mosaic of forests, baths, lakes, and bays protects one of the great concentrations of fauna in South America. After a visit to this area in 1912, Theodore Roosevelt wrote, "It is literally an ideal place where a field naturalist could spend six months or a year. Now sixty years later here I was in the Pantanal hoping not only to study its fauna, but also to encourage the Brazilian government to establish a national park here.

Jaguar banquet

Several black vultures took off from a capon where the female had dragged the capybara carcass. After eating only a part of the forequarters - the breast meat, the heart, the liver, and the flesh of a palette - she had left the remains. In this climate the capybara is edible for no more than two or three days, after which the meat becomes rotten and full of larvae. Still, the jaguars even when undisturbed spend only one night with each carcass. Perhaps food is so plentiful that the cats do not worry about their next meal, especially when their menu includes not only capybaras and ungulates but also a wide variety of other creatures: fishes, turtoises, sucuris (anacondas), caimans, quatis, otters and bugios ( howler monkeys ).

A cloud of flies followed me when I dragged the carcass from the capon. As always, the feline had killed the capybara with a precise bite to the skull. The jaguar takes the head in its mouth and with the canines opposite pierces the bone to the brain. This technique is noteworthy not only for the precision with which the canines pass through the bone in or near the ears, but also for the force required to penetrate almost an inch and a half of bone. Jaguars can kill even cattle by breaking the animal's skull with a primitive force unknown even in lions and tigers which usually kill large prey by asphyxiation.

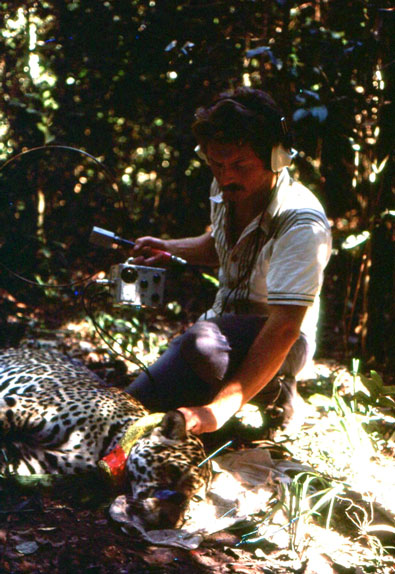

Peter Crawshaw monitors tranquilized jaguar. Photo: Peter Crawshaw collection

*This image is copyright of its original author

Each day thirty to thirty-five capybaras grazed along eight kilometers of beach where jaguars commonly hunted. What effect did predation have on these giant rodents?

To discover this we walked on the beach almost daily for two months, looking for fresh carcasses. The cats killed seven capybaras during that time, one-fifth of that small population. The impact of this predation was obviously so great that these rodents could not survive the pressure for long. However this result must be analyzed from a historical perspective. Many hundreds of capybaras existed in the region until 1974, when a severe flood submerged most of their habitat near the Paraguay River. The animals concentrated along the water where they soon began to die of disease - most likely African horse sickness, a form of trypanosomiasis.

The parasite for which these rodents are natural hosts remained in a latent state until the stress of overpopulation and lack of food made the disease virulent.

The region was still flooded during our study in 1977, and the disease still affected capybaras. Four animals in our sample were visibly weakened emaciated and covered with wounds, and several others appeared to be ill.

Arrest me if you can

Normally capybara populations can tolerate disease and predation because they are prolific breeders. Each female produces litters of up to eight cubs at least once a year but for unknown reasons few cubs were born or survived in Acurizal. Thus decimated by disease and hampered by a low breeding rate the population could not absorb the additional impact of predation. Fortunately for the capybaras the jaguars soon moved their hunting area to another part of the farm.

For details about the private life of jaguars, - their daily movement patterns hunting frequency and types of social contact - radiotelemetry had to be used. Capturing a jaguar and putting on a necklace with a radio transmitter should be easy I thought. It would only take hanging a piece of meat near a trail and camouflaging various snare traps around it to trap the animal safely and without posing a risk to it as bears and pumas are captured in the United States. The design of the loop is simple: the animal steps on a hidden trigger which fires a spring closing a steel cable on the feline's paw.

But the jaguars showed no interest in any of our baits dead or alive. In the mornings we found footprints headed straight for the trap site but they passed through them without even changing the stride. I tried to lure them with scent baits using the feces of another jaguar or sharpen their curiosity with a bird in a cage - without any result. Then changing tactics I eliminated the meat lures and carefully set the snares directly on the trails. The jaguars now stepped on the triggers but reacted so quickly when they felt the danger that they were able to pull their paws off before the loop closed. On the other hand, the loops worked very well with the cattle and releasing a 300 kg cow certainly provided very interesting moments.

Not only did the jaguars frustrate my attempts at capture they actually seemed to confront me: a female passed by our nets while we slept and a male put his prey - a capybara still intact - 90 meters from our camp. Although already angry I couldn't help but admire the animals' ability to crash. With its short sturdy head placed on muscular shoulders the animal gives an impression of strength rather than cunning and I had mistakenly underestimated it.

New attempts

Expedition with the dogs for jaguar capture. Photo: Peter Crawshaw Collection

*This image is copyright of its original author

Since my attempts to capture the jaguars with traps had failed, I decided to use traditional methods in Brazil to hunt these cats. In one of them the hunter floats silently in a boat near the shore at night periodically imitating the animal's husky and deep vocalization with a gourd. Attracted by the call the animal won't find another jaguar but the blinding beam of a spotlight followed by the deadly wound of a bullet. Another method is to chase the feline with dogs until he climbs a tree or acue in closed vegetation where he can be killed with a zagaia or firearm or according to my interest anesthetized.

Richard Mason an English foreigner living in Brazil owned the best pack of dogs trained to hunt jaguars in western Brazil where he used to take clients on expeditions until a federal law in 1967 prohibited hunting, affecting his business. He agreed to help me and arrived in Acurizal with five dogs and his mateiro Mr. Manoel Dantas with twenty-five years of experience as a professional guide and hunter in the Pantanal.

The master dog named Gigante, a castrated yellow mongrel walked in front sniffing the forest floor looking for a fresh track of the jaguars. The other dogs got excited pulling on their collars following the occasional bark of Gigante. Dantas then followed opening a trail with short strokes of his machete. "Hup, brriii," Richard would shout at intervals, stirred Gigante and let him know we were after him.

For hours on end then for days we traverse the entire area covered by the jaguars without finding any fresh footprints. During the months preceding the hunt we had spent some time at the Bela Vista farm north of Acurizal. Had the jaguars moved there in the meantime? I didn't think so. Where then were the adult female and her daughter?

One day we were in the remotest area of Acurizal, a shadowy forest in the narrow part of a valley between the mountains. Gigante was ahead - his barks saying he was interested but not too excited by some smell - while we followed slowly along the dry bed of a stream thinking of new areas to look for. Suddenly, Gigante yapped several times as if he were being attacked then silence.

"The dog was hurt! It could be a pecari, or even an jaguar!" yelled Dantas. We released the other dogs who were barking and they shot up the valley. Soon their barking merged into a continuous racket with only the resounding howl of Bagunça clearly distinct.

Sedated Jaguar

We hurried to follow the dogs crossing bromeliads with sharp thorns in a blind race to where they clustered around a tree leaning over the dry bed of a stream. Trembling with excitement the dogs jumped against the trunk and bit the hanging lianas. Lying on a branch about seven meters above the dogs there was chaos a young female jaguar strangely calm looking at us and the dogs. "finally we met" I said to myself. While I prepared a dart with a tranquilizer drug Dantas moved the dogs away tying them in a tree a few hundred meters from there.

As soon as the dart hit the feline's thigh we moved away to wait for the anesthetic to take effect. It then descended from the tree and disappeared into the undergrowth. Ten minutes later we followed her with just one dog finding her already sleeping at 100 meters.

To reward Gigante for his excellent service we brought him to the anesthetized jaguar. Even having the claws of the jaguar minutes before cut his body the dog just looked at the animal lying down without expression. We did not know then that this had been his last hunt that one of the wounds had produced an internal hemorrhage and that he would die later of infection.

"In other times, that animal would already be dead. I would already be taking her skin off" commented Dantas as we prepared to record her vital statistics. She weighed 70 kilograms and measured 167 centimeters from the tip of her snout to the tip of her tail. Its a small animal by Pantanal standards where jaguars are the largest in the world. Richard who had always carefully recorded hunting trophies told me that the average weight of a female was 75 kilograms and that the heaviest male captured by him weighed 119 kilograms. Peter and I then placed the radio."

George Schaller places a monitoring collar on a jaguar in the Pantanal in 1977. Photo: Peter Crawshaw collection

*This image is copyright of its original author

Epitaph for a jaguar (part 2)

Published in June 18th 2014 https://www.oeco.org.br/blogs/rastro-de-onca/28428-epitafio-para-uma-onca-pintada-parte-2/

Peter G. Crawshaw Jr.

Monitoring of the small female jaguar in Acurizal July 1978. Photo: George Schaller

*This image is copyright of its original author

The following text is a continuation of the first part of the article "Epitaph for a Jaguar" by George Schaller which narrates the adventures and misadventures of the first modern study on the jaguar done in 1978 by Schaller and Peter Crawshaw at the Acurizal farm in the Pantanal of Mato Grosso.

"One hour and fifteen minutes after the injection of the anesthetic, the jaguar staggered out of our field of vision still recovering from the effects of the drug. Although happy with the success of the capture I felt a vague restlessness that refused to take a conscious form in my thinking. Something did not fit: this animal was too heavy and its legs too big to be the young female from Acurizal that we had been following for months. And where was the mother?

A few days later our cook told us that in conversation with the wife of one of the farm's pawns she had learned that a jaguar had been killed in Acurizal the previous month. The death of even one animal would seriously affect the already small population and we were worried not only about the animals but also about our project.

Looking for more information Peter and I went to Claudio an employee who had shown interest in our study bringing small animals into our scientific collection and passing on information about footprints he found. We asked him about the dead jaguar. Mounted on his mule he looked over our heads at the distant mountains and said "I don't know anything, I wasn't with the entourage".

We then went to see João, a pawn ( rodeo guy ) with the wide and pleasant features of a Bolivian Indian. His eyes turned away from ours when we questioned him. "In some matters, I just have to obey orders," he spoke softly and turned his back.

Felix a long tangled bearded squatter was supporting a family with twelve people planting mandioca (cassava), bananas and other products. "I don't know anything," he said spreading his arms wide pretending ignorance. "I hunt a few deer, peccaries and armadillos. but never jaguars. I say only what I know."

Unable to break the conspiracy of silence we went to Filinho's shed, a fence contractor. A pack of mutts with their ribs showing up announced our approach frantically barking. Filinho listened to us and his eyes had no sign of regret when he frankly admitted "Yes, I killed the jaguar. I have nothing to hide. I hadn't said anything before because you hadn't asked me". He also said that Geraldo the farm administrator who occasionally looked after the interests of the farm on behalf of the absent owner had given orders to kill the jaguars. In Geraldo's opinion, cattle and jaguars cannot coexist. "There is a saying in Brazil", he once told us: "You can't whistle and suck sugar cane at the same time".

One evening Filinho had surprised the adult female in the carcass of a calf and killed her with a shot of 22 ( a handgun ). He sold her skin to a mascot owner of one of the commercial boats that sell and buy products along the Paraguay River. The leather/skin of a jaguar sells for about 100 dollars that of an Ocelot sells for 50 dollars, that of an Otter for 30 dollars and that of a Caiman for 3 dollars. (Translator's note: these prices are from 1978 and do not reflect dollar inflation until/of today).

In the Pantanal there is legal protection protecting the fauna but little enforcement to enforce the legislation and illegal hunters operate freely with impunity. In São Matias Bolivia near the border with Brazil, a man named Otis Paraguayo operates a tannery to process the hides of animals hunted in the Pantanal. Alfredo dos Santos and his two sons travel openly along the Paraguay River in a boat from which canoe hunters penetrate the flooded areas and return loaded with hides. Besides them there are several other intermediaries whose names are also known.

A military patrol once seized Alfredo dos Santos with the boat loaded with furs/skins and handed him over to civilian authorities. A few days later he was free again all charges dropped. When questioned the officer in charge replied "I don't want to be a dead hero." The border laws operate in the sparsely populated lands of the Pantanal; piranhas are competent to make corpses disappear.

When we clarified to Filinho that he could be arrested for killing a jaguar, even if authorized by Geraldo he responded naturally: "Well, if I go to jail one day I will get released and come back. Then I can forget that I have children and I can shoot Geraldo''.

In the middle of the night one of the pedestrians named Joseph came to the headquarters where we lived. First he asked for ethyl alcohol used locally to drink pure or mixed with milk and sugar. Then he apologized for the schedule saying that he was afraid to be seen with us especially by foreman Aníbal. He had the appearance of a vulture and a corresponding personality; all the local residents hated him.

Like Acurizal many farms in the region had killed two or three jaguars in recent times. In Bela Vista five had been killed in 1974. Four years later the population had not yet recovered only four individuals remained in an area of 94 km². One hunter killed 37 jaguars on one farm over a period of 12 years then he killed another 68 jaguars on another farm over 8 years.

Employees routinely kill jaguars, professional hunters bring in foreign clients on illegal hunts and commercial fur/hide/skin hunters are responsible for an unknown number of jaguar's deaths. There are still those who try to imitate Sasha Siemel, a hunter who with a rifle or with a sword killed more than 200 jaguars in the Pantanal between the 1920s and 1930s. "It is impossible to kill all jaguars " a farmer once told me presumptuously. "Some animals will never be caught in the pigeons."

I could have told him that ignorant words like those were probably spoken also for the United State's passing doves and for the quagga, a zebra-like horse from South Africa which used to be very numerous but were extinct in recent times by man. But I have only emphasized that the jaguar has already been extinct or drastically reduced in large parts of the Pantanal largely due to the persecution by farmers over the past 25 years. No species in which the female has on average only one cub every two years can withstand such pressure. Unless this local attitude changes only with a large national park can the species be saved in the Pantanal.

The ostensible reason to eliminate jaguars is because they attack cattle. In fact they do attack although they are responsible for only a very small percentage of the cattle that die each year. In one municipality of the Pantanal the number of cattle has been reduced from approximately 700,000 to 180,000 in six years due to a combination of disease, flooding and lack of pasture. After severe flooding submerged the pastures for months on end. As a result of poor cattle management on many farms only one cow in four or five can raise a calf.

While working at Bela Vista Farm we captured an adult female jaguar and monitored her for two and a half months until her necklace stopped working. We had contact with her for 35 days. During this period she preyed on only one calf a rate equivalent to twelve head of cattle per year - a low percentage especially considering that part of the slaughtered cattle are wild or feral or would have died from other causes.

This female in Bela Vista also revealed interesting facts about jaguar movements. Keeping uninterrupted contact with her day and night we discovered that this supposedly nocturnal feline often walked through the forest in broad daylight, although she was usually more active soon after sunset and before dawn. She remained inactive probably asleep, for about 8 of the 24 hours of the day. The daily distance covered ranged from 2 to 12 kilometers. Sometimes she stayed for several days in a small area especially if she had prey there. At other times she would quickly go somewhere far away as if she had an appointment to keep.

I liked to monitor this female at night alone except for the radio signal that connected me for a hundred meters to her, the silent and still forest under a lint of the moon. Listening to the night sounds searching for substance in every shadow, I was filled not only with suspense but also with a sense of fullness.

We followed the female of Acurizal too but I did it more as an obligation without joy trying to collect information about the size of her territory. We knew that with the two other dead animals we would soon have to look for another study area. Still, this female provided us with rare moments of pleasure.

Once shortly after noon Peter picked up her signal as she was moving through a gallery forest. We followed her discreetly never close enough to see her only the directional antenna on the receiver indicated her movements. She came out of the cool shade of the forest and plunged into the blinding sunlight on small rocky hills with sparse vegetation of low, crooked trees. She kept a steady step suddenly turning and turning towards us, the signal increasing in volume until Peter said "I can hear the signal without the help of the antenna".

About 100 m away she stopped in a ravine between two hills and, as we later discovered, she rested near a small puddle. There she remained for all the relentless heat of the afternoon and she was still there, the placid and constant signal when the so-called melancholy of a jaó announced the arrival of the night. We all remained there, the jaguar, Peter and I together in the darkness. I made a bed of dry grass and slept for a while leaving Peter to listen to the signal at thirty-minute intervals. Except for brief periods of activity the jaguar slept too showing no movement during the night. With the first hoarse vocalizations of a group of bugios ( howler monkey ) at dawn she moved quickly along the valley, her signal getting weaker and weaker until the woods took her away.

At our request an enforcement agent visited Acurizal to investigate the death of the jaguars. He also confiscated the skin of the jaguar Anibal had hidden in his home. Now for the first time I finally found her - the young female who had eluded me in life. The leather/skin with her sad beauty, the empty eyes, the bullet hole... I didn't want to keep that memory. Was this animal really part of the past? Among certain Amazonian tribes the jaguar represents the sun, an immortal being who since the dawn of life has been the protector of all life including that of man, and when he dies he ascends back to heaven to restart once more the cosmic circle of rebirth.

"And so in George's sad and bitter words but holding on to a hope in the future, the first stage of the pioneering project to study jaguars in the Pantanal was concluded. In August 1978, George and I left Acurizal, he returned temporarily to the USA and I to São Paulo to await the birth of my second daughter Beatriz. In July while still on the farm in the darkest period of the project we had received the visit of a Brazilian-Swiss doctor, Dr. Jorge Schweizer with whom he was already corresponding. Aware of the unsustainable situation in Acurizal he took us on his plane Cessna to Poconé and Cuiabá to talk with farmers and IBDF authorities, to decide new directions for the project. Through negotiations between IBDF and the Secretary of Agriculture of the State of Mato Grosso it was decided that until the definition of a new research area to continue the study of jaguars, we would be temporarily established in the Cidade Rosa Exhibition Park, 11 km from Poconé, whose infrastructure with several houses at the time was idle. Pompously we changed the name of the place to CEPEFAUNA - Centro de Pesquisas da Fauna do Pantanal Mato-grossense. George and I combined our efforts to study some of the main prey of the jaguar mainly the capybara and the caiman along the Transpantaneira highway then still in the process of implementation between Poconé and Porto Jofre.

In the next article taking advantage of texts translated from articles originally published in English, I will take the opportunity to reproduce an article that had considerable repercussion when published in 1986. The article written by me counted on the resumption of the jaguar project already in its new phase in the south of the Pantanal and the use of an Ultraleve airplane to monitor jaguars equipped with radio collars in a pioneering experience with state-of-the-art technologies of the time in the study of these cats".

TO BE CONTINUED...

RE: Modern Weights and Measurements of Jaguars - Dark Jaguar - 04-07-2020

Monitoring jaguars with Ultraleve ( ultralight in portuguese ) in the early 1980s (part 1)

Published in July 1st 2014 https://www.oeco.org.br/blogs/rastro-de-onca/28469-monitorando-onca-de-ultraleve-parte-1/

Peter G. Crawshaw Jr.

The author preparing to land the ultraleve Retiro do Corcunda, Miranda Estancia, Pantanal, 1983.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Continuing the format of the two previous articles, this article translates an article written by me originally in English "Top cat in a vast Brazilian marsh" and published in Animal Kingdom Magazine in September/October 1986 and republished in 1988 (Ultralight Flying!, February (144): 16-19) and in 1989 (Current Science, 74 (11): 4-6). The article continues the story of how we left the Acurizal farm to resume the study of jaguars at Miranda Estancia in the south of the Pantanal with a period between the two projects we spent in Poconé between August 1978 and April 1980.

"Over the noise of the engine, the beeping of the radio signal increased in volume in the earphone. As I made a downward turn to check where the signal came from Dr. Wonderful, one of our radio-collared jaguars emerged from a bush capon into the open field 60 meters below me. He stopped at a cattle trail looked directly at me for a few seconds and continued walking apparently oblivious to the strange noisy colored bird flying above him. Happy and extremely excited I turned east and started back to our research station. This was most likely the first time a jaguar had been seen in the nature of an Ultraleve an experimental plane aircraft capable of flying much more slowly than any other aircraft. Its incredible driveability allowed me a much more intimate view of the Pantanal a region in southwestern Brazil that is home to one of the highest concentrations of Neotropic fauna.

This unusual encounter of mine with a nearly adult male jaguar occurred during the first study of the species. Appropriately our research funded by Wildlife Conservation International (WCI, a division of the New York Zoological Society) and the Brazilian Institute of Forest Development - IBDF (the forerunner of IBAMA), was initiated by Dr. George Schaller a world-famous zoologist who had previously conducted the first studies of other large cats such as lions, tigers, and snow leopards. I had been hired by IBDF as the Brazilian counterpart of the study in early 1978 still at the beginning of the project.

Our house at Corcunda, Miranda Estancia, 1980. Next to it there was another one which served as a residence for Howard and also as a laboratory.

*This image is copyright of its original author

The Pantanal covers about 140,000 km² along the upper course of the Paraguay River in the states of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul. The terrain varies from flat to undulating with extensive savannas dotted with palm trees and capões of semideciduous forests, gallery forests along watercourses and different configurations of cerrado. Most of this area is flooded annually between December and March when only islands of higher ground remain out of the water. In May the flood waters begin to recede and in October/November only sparse puddles remain. A warm, humid climate predominates most of the year with temperatures rising above 40 C but cold winds from the south can bring thermometers down to below zero between June and August. Seasonal flooding and the absence of roads have so far discouraged larger developments in the region. Cattle ranching is the main economic activity with herds totaling about six million including zebu cattle and Asian buffalo.

Our study was initially located at the Acurizal farm on the western edge of the Pantanal near the border with Bolivia. For 16 months we followed the movements of several jaguars living in the area and collected information on the flora and fauna including capybaras, the large rodents that constitute one of the main prey of jaguars. The study was going very well until we discovered that farm employees had killed two of the jaguars we were studying ( the ones on the post above on "Epitaph for a Jaguar" Animal Kingdom Magazine April/May, 1980 ). The death of these animals broke the social structure of the already small population and forced us to seek a new area of study.

By indication of a common friend we chose a new area in the south of the Pantanal in a place called Corcunda a retreat in Miranda Estancia a cattle ranch of 248 thousand hectares. The retreat was 20 km from the farmhouse and 56 km from the city of Miranda, the closest city. We chose this place not only for its beauty with the forest on the edge of a bay but also for being the last point on high ground that could be reached by car. From there on the lower part of the Pantanal was extended a favorite habitat for jaguars. As to give us luck in our first visit to the place we found footprints of a jaguar on the edge of the bay.

When I moved to the farm George had already left the project to begin his study of the Giant Panda in China leaving researcher Howard Quigley who had been hired by WCI to replace him in Brazil. Our first mission was to build the houses and a hangar and landing strip for the Ultraleve ( mini plane ).

Rustic hangar built to house the ultraleve, Retiro do Corcunda, Pantanal de Miranda, 1983.

*This image is copyright of its original author

Life in Corcunda was easy. We shared the retreat with farm workers and their families who occupied two other houses. I was always impressed by how my wife Mara and our two daughters Danielle and Beatriz adapted to the life on the farm. Born and raised in Porto Alegre the capital of Rio Grande do Sul, Mara suddenly found herself running around with agouti and peccaries attacking her vegetable garden and sucuris ( anacondas ) eating our chickens. When later we had to send Danielle to school in Porto Alegre with her grandparents she had trouble convincing her classmates that their stories were not lies.

Flying over the Pantanal in our ultraleve with one-person capacity, Howard and I had access to the most remote areas in a way not even the farm pilot with the Cessna 182 Skylane knew. Having our own plane also saved us the regular commercial air taxi expenses for the locations of the jaguars necessary for their monitoring. It allowed us to check their movements daily and sometimes we could even discover carcasses of slaughtered animals from the air.

Privileged view

It is difficult to describe the sensation of slowly flying over an inhospitable wild region sitting in the open "cabin" of our device with the first rays of the sun starting to heat up the fresh morning air. I watched groups of howler monkeys below feeding on the tree tops, Pantanal Deers with water up to half their legs, choosing different species of the aquatic vegetation, families of capybaras grazing peacefully along the water courses and caimans warming up in the sun.

Female of Pantanal deers (Blastocerus dichotomus).

*This image is copyright of its original author

We soon fell into a daily routine. Using the ultraleve in the first two hours of light we would locate the jaguars with necklace, selecting one of them to follow on the ground. Then using horses or canoes depending on the season drought or flood we spent 3 to 4 hours to reach the place where the animal had been located earlier, sometimes just to find that it was no longer within reach of the equipment. But we usually found the signal more than 2 km away and made a fly camp with our nets. Every 15 minutes we would record the ambient temperature and movements and change in activity of the animal. These cats stay in one place for a long time between two and four days only if they have killed a large prey like a peccari or a capybara and if nothing upsets them. On those occasions we were able to maintain contact for up to 72 hours. Often, however, jaguars spend only one night with a carcass.

The ultraleve was a valuable tool but sometimes it brought us moments of anxiety. On a windy morning in October 1982 Howard took off from the Piúva retreat track to locate the jaguars while I prepared our horses and equipment for the day. After two hours without him returning I knew something had gone wrong as the device had enough fuel for only an hour and a half at most. Through a complicated network of messages passed by vehicle, telephone and horses I was able to call an air taxi driver from the nearest airport in Aquidauana. In the middle of the afternoon the pilot arrived and we immediately left looking for Howard. For this we used the same system that we used to locate the jaguars since I had installed a radio transmitter in the ultraleve itself precisely for an emergency like this. I could only hope that Howard had turned the transmitter on.

We flew for an hour before I could detect a very weak signal. Using the directional antennas in another five minutes we could see the device and Howard he seemed fine. Using broken branches on the ground he had written "H2O" and "FACTION" in large letters. The plane had landed on a stretch of pimply shrubby vegetation in a part of the farm rarely visited even by rodeo guys.

The pilot and I flew back to Corcunda and I prepared a backpack with several items including a mosquito net and raincoat, sheet, flashlight and batteries, cookies, repellent and even a Time magazine. I filled a plastic gallon with water and we flew back to the crash site. Fighting the wind I opened Cessna's door and managed to throw the backpack hitting a dense bush that I had looked at. We found out later however that the gallon had broken when it hit the ground and the water had leaked out. Only the next morning when the pilot threw him five green coconuts and a note warning that we were on the way to the rescue was Howard able to drink.

Riding on the horseback it took us four hours to get to the scene. After drinking a pint and a half of tererê (cold chimarrão) Howard told us what had happened. He was flying low to gauge the location of Eva, one of our newest jaguars when a sail cable came loose because of the engine vibration causing it to go out. With no time to choose a more appropriate location for the emergency landing he pointed the plane at a good-sized bush to make up for the fall. He suffered only a knee injury from the crash and the plane had its propeller shaft slightly bent.

When we started going back it was interesting to find Eva's tracks over Howard's footprints where he had walked the day before. Probably driven by curiosity she must have come during the night to inspect the strange intruder in her territory.

To pick up the Ultraleve,four days later I returned to the site with a farm worker and a digger. By mid-afternoon the tractor driver had cleared a small runway and I took off and I was not very happy about it. The bent axle made the plane shake so hard that I feared his parts would start to come loose and fly by themselves. I climbed into a closed spiral higher and higher over the small runway in the middle of that desolate immensity deciding whether I should continue. The sight of the white houses of the Carrapatinho retreat shining in the distance helped me in my decision and holding the parachute on my lap I pointed the plane in that direction.

After an eternity of 20 minutes all the time I was forcing my view looking for open areas where I could land the plane in case of an emergency I managed to get to the retreat without any further problems. But that was not the end of that story yet. That night a wind storm broke the ropes with which I had tied the ultraleve to the ground and threw the headgear over a fence. The aluminum tubes were twisted like noodles. In order to get it in flight condition again we had to order parts from Rio de Janeiro and hire a specialist mechanic who came from Brasília".

Jaguars capture techniques and the young Mr. Wonderful. (Part 2)

Published in July 2nd 2014https://www.oeco.org.br/blogs/rastro-de-onca/28471-tecnicas-de-captura-de-onca-e-o-jovem-mr-wonderful/

Peter G. Crawshaw Jr.

The following text is a continuation of the first part of the article "Top cat in a vast Brazilian marsh", published in Animal Kingdom Magazine, September/October 1986, and re-published in 1988 (Ultralight Flying!, February (144): 16-19) and in 1989 (Current Science, 74 (11): 4-6). The article tells the story of the study of jaguars at Miranda Estancia, in the south of the Pantanal, with a period between August 1978 and April 1980.

Jaguars are so discreet in their habits that the only time we had direct contact with them was during the captures to place the necklaces obviously the most exciting aspect of our work. We adopted one of the traditional methods of hunting these cats in the Pantanal using specially trained dogs that chased the animal until it climbed a tree or watered it in a stretch of dense vegetation. Each capture was a new event and no participant neither the jaguar nor the dogs, horses or people reacted in the same way.

The day we captured Dolly an adult female we were on the trail of another female, the Mother to change her necklace whose battery needed replacing (the duration is a little over a year). Our group - Mr. Jaime, foreman of retreat Piúva, Darlindo a dog handler, Howard, and I was crossing a stretch of flooded field when Mr. Jaime saw a jaguar coming out of a small forest captain and running into the nearby forest. After testing the frequencies of our harnessed animals I was sure that this was a new animal, without necklace.

We released the dogs and a pandemonium broke out. Barking in frenzy they immediately picked up the scent trail (the "beat", as they say in the Pantanal) left by the jaguar and entered the forest. Tying the horses in the shade we opened a trail through the closed vegetation hurrying to get close enough to the dogs to hear their barking. Suddenly the barking changed tone, from the continuous howling characteristic of the race turned into short and excited barkings: the jaguar had perched, it had climbed a tree! Darlindo's experienced eyes soon located it squatting on a fork mimicking the dense foliage. He and Jaime attached the dogs to their collars and tied them at a distance from there. Howard and I simultaneously threw two darts, one on each part of the animal's muscular quarters and walked silently away so she could get down before the anesthetic took effect.

Dolly female jaguar on the tree fork. Photo: Peter Crawshaw collection

*This image is copyright of its original author

When she leapt to the ground already dizzy she started running in circles. Twice she came a little over a metre from me but she changed direction without any sign of aggression when I yelled at her and clapped. Before we could throw another dart she disappeared into the undergrowth. Soon after Darlindo again found her lying still, but yet alert under a bush. One more dart, this time in the palette and in a few minutes she was sleeping harmlessly at our feet. When we examined her we discovered that this 75 kg female was in heat (estrus) she still had semen over her swollen vulva. Small open cuts on her head, neck, and shoulders attested to her recent love encounter. We adjusted the radio-collar on her neck safely and waited at a prudent distance until she recovered from the anesthesia and moved away from the site.

The capon from whom she had left revealed more surprises. Not only did we find fresh footprints of an adult male there mixed with hers but also the carcasses of a female sub-adult Puma and a male sub-adult Tapir. Both animals had been destroyed in the back of the head. The jaguars were probably eating the tapir when we interrupted their meal with our arrival. Marks on the grass indicated that they had killed the tapir in another capon about 60 meters away and dragged it over to where they had killed the Puma, but not for food. This reminded me of an occasion in Acurizal when a pair of jaguars had apparently killed a midget anteater as a joke, as they had merely bit him in the back of the head and abandoned him. George Schaller had speculated that this might be a way to reduce the tension and aggressiveness between a pair while the female is still not very receptive.

During our three and a half years in Miranda, we equipped seven jaguars, from a population we estimate at about 52 animals. We were lucky to capture an entire family group composed of an adult female the Mother and her two sub-adult cubs Felicia female and Dr. Wonderful male. Two years later we still captured another male offspring of that same female. Being able to monitor this family gave us new knowledge about the social organization and area ownership system of the largest feline in the Americas.

In March two months after her capture Felicia and her brother with 18 months old separated from their mother who immediately began to cover a larger area apparently looking for a male. Our assumption was confirmed when some day between July and August she gave birth to a new litter. (The gestation period of a jaguar is approximately 110 days). Later we captured and equipped one of these cubs, a male that we named as Felix. Based on the footprints we found we were reasonably certain that the mother had given birth to two cubs again which seems to be normal for jaguars.

Felix male soon established a new territory close to her mother's. Dr. Wonderful male headed east looking for unclaimed territory. The period of dispersion for a male is generally difficult. He is forced to leave his native area expelled by his mother until as an adult he establishes his own territory. During this time he has to cross unknown terrain risking finding other resident animals which could harass him. At the beginning of this journey I found Dr. Wonderful male in a woodland capon completely isolated by the flood. It was late March 1982. I set up my net about 100 meters from where he was feeding on a giant anteater at the other end of the capon and prepared to spend a long night monitoring his activity.

Driving camp monitoring the jaguars at Miranda Estancia, Pantanal de Miranda, 1982. Photo: Peter Crawshaw collection

*This image is copyright of its original author

At dusk, another jaguar burst nearby in the same capon we were in. I knew it was a female from the quick succession of short roars. A male's vocalization differs by being much slower and more severe. The next morning I confirmed that it was a female by measuring her footprints - the footprints of a male are larger and more rounded with the fingers more separated from each other. After some hesitation Dr. Wonderful male responded with apparently shy roars and for the next hour they communicated with each other, the female's roars becoming more impatient and the young male's more reticent.

Two hours later Dr. Wonderful male passed by me making a noise in the water when he passed about 30 m from my net. His radio signal slowly disappeared in the night taking my sense of security with him. As soon as he left the female went to where he had been and until two o'clock in the morning she wandered restlessly around disturbing the dawn's silence with her rough roars. Then the sound of an adult male echoed from afar to which she responded and then apparently went to meet him.

This incident gave us a glimpse of the importance of vocalizations in the jaguar's intra-species communication. On one hand the adult female and the young male avoided direct aggressive contact which could have resulted in disabling injuries to one or both animals. On the other hand the female's calls had served to attract an adult male from a great distance. This last case seems to be the main function of the vocalizations of the species in the Pantanal since we commonly heard these calls during the reproductive season from December to May.

For the next two months I followed Dr. Wonderful male's movements as he left his home area. In July five months after the separation from his family he finally settled in a new territory 30 km east of the territories of his mother and sister. We had no further evidence that he associated with them again. In December 1983 just before our project ended I found him lying next to an adult female without necklace. At the age of just over three years I was sure that he had secured his place in the farm's resident jaguar population.

Photo: Peter Crawshaw collection

*This image is copyright of its original author

In 1985 researcher Alan Rabinowitz of the Wildlife Conservation Society completed a 20-month study of the jaguar in the forests of Belize Central America (see "In the Realm of the Master Jaguar," Animal Kingdom March/April 1986). Preliminary comparisons with our results show the adaptability of a species that is distributed from Mexico to Argentina.

In the most open habitat of the Pantanal jaguar territories averaged 142 km² almost four times more than the 40 km2 found in Belize. While our jaguars fed mainly on large prey such as capybaras and peccaries the most important food in Belize was armadillos. These differences are probably related to the fact that jaguars in the Pantanal are twice as big as those in Belize. The average weight of six adult males in Belize was 58 kg while five females from the Pantanal averaged 76 kg. Dr. Wonderful our only male even as a subadult weighed 70 kg at 22 months and in the Pantanal there are claims/reports of males over 128 kg.

The differences in habitat also influences the area tenure system. In Belize females had small exclusive territories. Females in the Pantanal had large overlapping areas during the dry season but during the flood each occupied almost exclusively an area of only one-tenth that used during the dry season. The more we learn about these types of geographical adaptation to local environments the better we can plan comprehensive management strategies.

Jaguars are protected by laws in almost every country where they still occur but in general they are still hunted for their skins or as trophies. Employees on cattle ranches still kill these felines ostensibly to protect cattle from predation. But while jaguars do kill cattle this percentage is only a very small part of what is lost because of diseases, parasites, floods and other factors.

Habitat destruction represents another major threat to the species. With each passing year, the forests that shelter and protect these magnificent animals diminish more in the face of the inexorable advance of man and development. Most of the Pantanal is located on private properties. Only two areas are protected by the federal government: the 138,000-hectare Pantanal National Park, near the border with Bolivia and a small island on the Paraguay River near Cáceres the Taiamã Ecological Station. Even with these sanctuaries however the future of the jaguar in the Pantanal is still uncertain.

Large carnivores are particularly susceptible to extinction several of them - the grizzly bear, the tiger and the snow leopard for example have already been eliminated from vast areas of their original distribution. These animals occupy the top of the food chain and protect large enough portions of their distribution areas to ensure sustainable populations of these species would certainly help the survival of many of the species below them in the pyramid. Even if only for this reason jaguars and other species like them should be considered and treated as symbols for conservation. According to John Weaver, national coordinator for the American grizzly habitat program their survival "will be a test of our commitment to wildlife and wild places, an account of our willingness to share a little of this small but beautiful Earth on which we live with our wild neighbors.

Pantanal: the adventures to recapture Dr. Wonderful

Published in December 10th 2014 https://www.oeco.org.br/blogs/rastro-de-onca/28825-pantanal-as-aventuras-para-recapturar-dr-wonderful/

Peter G. Crawshaw Jr.

Introduction:

Taking advantage of the fact that I have organized material to resume the work in my book (one day it comes out...) reviewing old field notes, I will present here more information on the first study of the jaguar already in its second phase at Miranda Estância, MS, in the early 80s. Nowadays ties made with steel cables have been considered more efficient for the capture of big cats and the method has been improved for use in lions, tigers, leopards, pumas, and in our jaguar as well. There are now several well-trained teams in Brazil to use this technique which in addition to improvements in the preparation of the loop itself mainly includes the parallel development of a system of transmitters used in the loop which warn when it was fired. Time is a crucial factor for the safe use of the technique as the risk of injury to the captured animal increases directly with how much it remains trapped in the loop. The shorter the time the less chance of the animal being injured. For this the responsible team must have a veterinarian with experience in the sedation of large cats and ideally also a biologist for the correct procedures in biometrics and collection of biological material for sanitary and genetic studies. And the team has to be prepared to go as soon as possible to the loop fired check if there was really the capture. If it occurred the animal must be immediately anesthetized and taken out of the loop at any time, day or night, rain or sun. By the way this is an extremely important precaution that the places chosen to set the snares are protected from direct exposure to the sun to avoid the risk of hyperthermia and that it is clean of vegetation or branches in which the animal can snuggle or get hurt.

However, as we narrate below at the time we started our study the method traditionally used for the capture (and generally hunting) of our big cats were dogs specially trained for this purpose. With a well-trained pack of onceiros dogs it was possible to program extremely efficient captures and mainly for this reason jaguar populations in the Pantanal (and other ecosystems as well) were seriously threatened. As already reported the services of a former hunter with his dogs were used for the first captures of the collared animals in the project in Acurizal. With these positive experiences one of the first steps I took when restarting the study at Miranda Estancia was to begin to form a pack of the project itself to gain independence at this crucial stage for the study. First borrowing dogs with experience and adding to them dogs of good origin that were donated to me. In this process I had an extremely important help from João Carlos Marinho Lutz, owner of one of the most beautiful farms I have ever known in the Pantanal. Santo Antônio do Paraíso between the Itiquira and Correntes rivers in the city of Rondonópolis. He helped me to obtain onceiros dogs that I used in the first captures at Miranda Estancia which allowed the subsequent success of the project. I even had 28 dogs of my own for use in the project some very good and others not so good. But together they guaranteed with some efficiency the captures and recaptures that made it possible to bring the study to a successful conclusion.

With that introduction. I'll narrate the case below